Savage Symposium: FEAR ITSELF & FLASHPOINT (Part 3 of 3)

/Given the recent news of an upcoming psuedo-reboot-something-whatever, that certainly seems to be the case with FLASHPOINT. DC is constantly trying to "fix" its universe, but... Well: does anyone remember why they're constantly trying to fix their universe anymore? Can anyone tell me what's broken about it that needs constant fixing? Does anyone still care about seeing that universe get fixed? I feel very alienated from DC crossovers because I don't care at all, even a little, about the container that holds the DC characters, certainly not as much as DC expects that I do.

With FLASHPOINT, I think the speculation that Graeme had on one of Jeff & Graeme's GUH WHY? podcasts-- which I, of course, take as gospel-- is FLASHPOINT will end with Barry Allen mis-remembering the DC universe, with his mis-rememberings forming the new continuity. If I remember correctly, I think that was Graeme's guess. Which... Is that what they're going to do? I don't know, but it sounds equally plausible with any other fucking thing we can think of, doesn't it? "FLASHPOINT will end when fart-leprauchans rebuild the DC Universe from soiled panties found in a Japanese vending machine." That would mean about as much to me as anything else, at this point.

I mean, I can't say I don't understand the impulse. I guess I probably have my pet belief of how-I'd-run-DC, in a way that I absolutely do not have with Marvel, in the slightest. I think DC has always seemed so chaotic and pieced together, that it ends up inviting its readers to play Railroad Tycoon: Comics Edition with the company, in a way that maybe Marvel doesn't. So I can see how it'd be tempting to get your fingerprints on everything if you're running the show. But... I think it's a case of people misjudging their greatest strength: because of the fact that DC is a more chaotic and pieced-together universe than the Marvel universe, almost every single great superhero novel has been done for DC. After so many years, Marvel has, what, SQUADRON SUPREME and MARVELS. That’s about all I can think of. Whereas DC, you have the major Alan Moore superhero comics, all the best Grant Morrison comics from ANIMAL MAN on, ENIGMA, NEW FRONTIER, THE GOLDEN AGE, RONIN, Goodwin-Simonson MANHUNTER, DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, BATMAN YEAR ONE, SANDMAN, SANDMAN MYSTERY THEATRE, BLACK ORCHID, ALL STAR SUPERMAN, the good bits of STARMAN or v4 LSH, and so on. DC may have cancelled CHASE and MOSAIC, but Marvel never published either, you know? I would have to attribute some of that difference in the numbers to DC being a far more patchwork universe, that the patchwork quality lead to it being a place that could contain wildly disparate takes, strange voices, rogue editors, whatever, in a way that Marvel has never been able to match, to the present day. The whole urge to force the DC Universe to “make sense” ... I don't think I can reconcile it with how I'd evaluate DC's strengths...

So: Is the organizational structure of the DC universe a conceit you still have any interest in? If this is something that's completely apart from your set of interest, if you're more of a manga/art-comic reader, how do you regard this discussion? Is it wholly weird & alien to you or is it consistent with what you'd expect mainstream comics to be like? Also: what's wrong with DC's characters that I'm missing? Have you been angry for the last 30 years that Hawkman doesn't "make sense" or something? Or what do you want to see fixed in this next reboot? Is there some particular change to the DC universe you've got your fingers crossed and are hoping to see? One of my all-time favorite Batman comics is an Evan Dorkin one-panel comic from the inside front cover of an old issue of DORK, where the one-panel shows Two-Face flipping a coin and saying to himself something like "Tails! That decides it-- tonight, Harvey Dent fucks men." I would like for that comic to be in continuity after the reboot in September. Can we start a petition? (Also: I think Lex Luthor should be the world's scariest criminal again, instead of a rogue CEO lame 1980's bullshit character. Also: they should do an Absolute edition of "Luthor Fights for Good" from ACTION COMICS. Also: in the rebooted DC universe, girls should like me. Awwwww).

BRIAN: I think that the instinct that things must “make sense” is more that they don’t contradict themselves. Clearly, if you invest so much of your time/self in following a fictional universe, you want the various pieces to “add up”

I think some people might have some particular want list of changes -- “Man, I wish Babs Gordon was still Batgirl” or whatever -- but I really do think that most people are just looking for the consistency that “the sun does, in fact, rise in the east”.

The problem with a shared universe is that the what is “east” in one strand of it might be “north east” in another. In a for example, post-Crisis, Wonder Woman wasn’t actually a founding member of the JLA -- she didn’t come to “Man’s World” until several years after the JLA was formed, for whatever reason. But we have the comics where she was there fighting Starro the conqueror or getting turned into a tree, or whatever else alongside J’onn. How do you “fix” that?

Someone (Waid, I think?) thought, “Well we can just replace Diana with Dinah (the Black Canary), and it will all be close enough” - and for most things, it probably is. But Black Canary is actually the daughter of the 1940s BC, and if that’s still true, then what happened to the story where they crossed from Earth-1 to Earth-2, because if that didn’t happen, then....

And so on and so forth -- the “continuity implants” end up having a domino impact on dozens of OTHER characters and events.

The problem with a character like, say, Hawkman, is that it is really hard to reconcile the Reincarnated Egyptian Prince version with the Space Cop From Thanagar version -- mostly because Thanagar has, y’know, invaded earth in INVASION or whatever. Dominoes, tink tink tink thud.

Do those things ACTUALLY matter when you’re talking about a shirtless guy who flies through the air to beat the shit out of people with medieval weaponry? Well, no, probably not, but there’s a jarring discordance that hums in the background and makes it hard to have that all important willing suspension of disbelief.

It’s like.... hm, it’s like have you ever had a dream and you’re totally following along, then something happens in the dream that makes you say “Wait, that fire hydrant is green!” then you know it is a dream, and the whole thing unravels in your mind, and you wake up suddenly feeling just a little askew? Balancing continuity across scores of characters and scores of books and scores of years is just like that. We’re “willing to accept” that, say, Dick Grayson has only aged 12-15 years in the last 75, but that Bruce has only aged maybe 7 or 8, because that’s the kind of cognitive dissonance that doesn’t jar us out of the dream. But Hawkman? “It’s a floor wax AND a dessert topping” is just one step too much.

This is what gets me about the assurances that “It isn’t a reboot! It’s a relaunch!” for NuDC -- if it isn’t a reboot, AND if they’re changing some/many/all details about some/many/all characters, then you’re starting from a cognitively dissonance-filled place. It is almost certain that we’ll have to look at SOME of the bits as “pre- and post-Flashpoint” which means that you’ll have to explain Flashpoint to explain the character, which then means you’ll also have to explain COIE, and how this is the fourth try at having Hawkman “make sense”. If you’re NOT doing a “hard reboot”, then a certain amount of your forward momentum will have to be spent on explaining where you do or do not know the previous versions. There’s a tiny handful of creators who can thread that needle adequately, but I can not see how on earth this could work across a line of 52 comics.

JEFF: As somebody who used to be really into continuity and no-prizes and what have you, I can safely say I now give less than two shits about that kind of thing, except where the always-difficult-to-gauge “so-and-so is/isn’t acting in character” (also known as the infamous “the real Batman wouldn’t do that” argument my wife finds so hilarious) comes in.

In fact, I think it’s pretty apparent that a consistent comic book universe can only go so far -- thirty years, maybe, at the most? -- before it collapses in on itself due to contradictions and paradoxes. I’m now more enthralled by the way in which both the Marvel and DC universes have conceptually become analogous to post-first world countries, structures that have to cannibalize past resources in order to continue to function, areas where new buildings are built on top of the old. Cultural palimpsests. Have you ever played World of Goo, and had to pull critters out of your tower of critters in order to get it to the right height and had the whole thing collapse? These days, the two universes remind me of that.

ABHAY: My whole life is a World of Goo.

JEFF: So I really don’t have much interest in the organizational structure of the DCU except in an insider baseball kind of way. And in that way, as long as it doesn’t destroy the direct market, I find this potential restructuring kind of interesting: I feel like someone sat down and seriously tried to figure out why people are watching movies and playing videogames featuring these characters but not reading the comics.

Maybe that someone was wondering what moved the needle so visibly and obviously when the trailer for Watchmen came out and suddenly you hundreds of thousands of copies being sold, but you’re lucky to get even a portion of that action after The Dark Knight, a much larger movie? Of course, we know it has everything to do with Watchmen’s quality and the fact that the trailer called the book “the greatest graphic novel of all time” but maybe someone somewhere actually had to explain to some higher-ups why a negligible success can sell tens of thousands of graphic novels and one of the biggest movies of all time can barely sell any.

In a way, I like the idea of DC sitting down and trying to remove the obstacles keeping a fan of the movies and games from picking up a comic book. I think they’re making a ton of mistakes, of course -- misunderstanding the role of quality, overestimating the need for synergy, ignoring the deeply entrenched disfunction in their editorial offices -- but I appreciate they’re actually thinking about what to do. As long as they haven’t decided one of the obstacles to getting new people into comic books are the comic shops, I don’t really care too much what they do or un-do or re-do to make it work. I’ve lived through worse things happening to comic characters I like than what they’re promising now.

ABHAY: It’s kind of fun that DC’s version of the Age of Apocalypse is making way for a new DC headed by Bob Harras where star comic creators like Dan Jurgens, Scott Lobdell, Rob Liefeld, Fabian Nicieza and Ron Marz can work on characters like Voodoo, the stripper-hero from WILDC.A.T.S. (Covert Action Teams). I don’t want to read any of their comics-- but I do want to watch THE EXPENDABLES with them, so you know-- bittersweet, pretty bittersweet. I guess people who miss the 90’s are happy-- if MC Hammer or Gerardo read DC comics, they’re both probably thrilled; if I’m Scott Lobdell, I’m waking up every morning praying that Gerardo isn’t dead-- that’s all I know.

JOG: Woah, whoa - OMEGA THE UNKNOWN, the Jonathan Lethem one! I’d put that up there with the big “superhero novels,” definitely. Maybe it needs more time to steep? I got irrationally agitated at the bookstore today flipping through the paperback edition of CHRONIC CITY and noticing that it wasn’t listed among Lethem’s works in the obligatory By the Same Author bit up front. It couldn’t be that he used a co-writer on the script - KAFKA AMERICANA is noted, in collaboration with Carter Scholz (whom we all know best, of course, as one of the premiere early writers for THE COMICS JOURNAL), so maybe it’s a publishing thing?

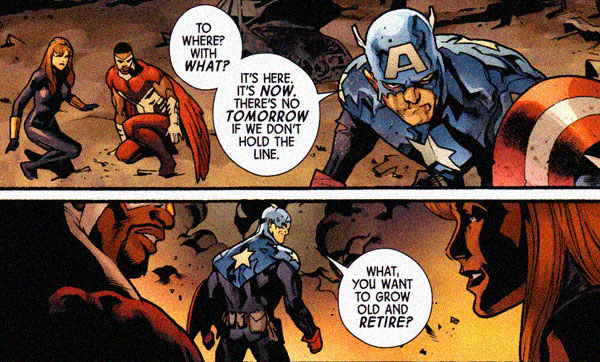

But anyway, here’s something I’ve been chewing over - I’m not generally interested in the organizational structure of the DCU, but I actually am in this instance, because I think it syncs well with what I’ve picked up as Johns’ continuing themes as a writer. I was discussing this with Sean Witzke on Twitter the other day - the final page of FLASHPOINT #2 is like something straight out of RUINS, Warren Ellis’ ultra-sardonic 1995 ‘response’ to MARVELS, positing a realer-real world superhero continuity where radiation gives people cancer instead of superpowers. And while it functions as mostly a dark joke, there’s something really serious about it too, because it’s not just a ‘ha ha superheroes are so dumb’ kind of thing - it’s a lament, a hyperbolic cautionary tale about adding too much focused ‘realism’ to superhero concepts, because the more you do that the more evident it becomes that actually living among superheroes would completely terrifying and awful. And I think about this whenever I’m reading superhero comics like FEAR ITSELF, with its global calamities and assaults on population centers, only the latest of so many - I’d fucking riot too!

That effect, I think, is what concerns Johns as a very devoted superhero writer. Because really, to say all of the ‘big’ recent DC crossovers are concerned with superhero mechanics -- and I’d agree with that -- is to say that Geoff Johns and Grant Morrison are, because they’re the headlining writers. You don’t get a lot of talk about Morrison as supplicant to the state of the DCU, however, because his invocation of such is hardwired into the broader evolutionary theme that marks so much of his work across media and genre. Johns is more of a strict company man, and a much more literal writer than Morrison -- was it our David Uzumeri that coined the term “Johnsian Literalism”? -- so it’s perhaps easier to process his own themes as merely the Hand of the Market at work, but think about it: of his big crossovers, INFINITE CRISIS and BLACKEST NIGHT, the threats as I understand them (having only read ‘of’ INFINITE CRISIS via essays and the like, I’m warning you all now) are corporeal avatars for problems facing superhero comics, respectively the desire to return the superhero world by force to a presumed ‘better’ state, and the return of dead characters as atrocious mockeries (an idea not so far away from some of the stuff Garth Ennis got into with THE BOYS).

Given this, with FLASHPOINT #2, I wonder if Johns’ plan is to pit superheroes against the world itself, a shitty state of being where Batman is crazy-violent-in-a-bad-way and ‘royalty’ characters mostly desire blood-soaked conquest and where getting doused in chemicals from an electric blast wins you third-degree burns from head to toe. The villain of FLASHPOINT -- and hey, I’m speculating!! -- might well be Reality as a potentially wicked factor, and thrashing Reality would be a suitably Geoff!Johns! way of resetting the universal status quo.

I could be entirely wrong, obviously, but that’s the way the DCU fits into my reading of FLASHPOINT, to answer your question - as complimentary to the ongoing themes I’ve sensed as an admittedly none-too-thorough Geoff Johns reader. I still think the little detours to Wonder Woman and Aquaman in issue #2 are more of a distraction than anything -- particularly in that Johns is going all DEATHMATE with the action, where characters long ago established as awesome fighters are checking out like punks left and right because it’s an alt universe -- and that’s about half the comic right there, so I can’t say it’s fantastically compelling on the whole, but I’m getting a bit more out of it than I’d expected. Shame it came out on the same day as HELLBOY: THE FURY #1, though, ‘cause that’s how I like my End of Days superheroes to roll.

JEFF: I think that’s a really lovely analysis, Jog, and I’m inclined to agree. My only problem is that Johns has repeatedly shown himself able to talk the meta-talk but very unwilling to walk his meta-walk: Johns followed up that commentary in BLACKEST NIGHT with the endless “hey-who-else-can-we-bring-back-from-the-dead?” adventures in BRIGHTEST DAY. And what looks more like the “return” of DC’s heroes to a better state by force than those 52 new titles awaiting us at the end of FLASHPOINT? I think it makes a lot of sense that Barry Allen will end up ushering a new “age of wonder” at this event’s end, mirroring the way his helped usher in the start of DC’s (and comics’) Silver Age, but I can’t help but suspect what we will see in that new age of wonder will be exactly the same as what we’re seeing now. Johns may have the capacity to talk about things being different, but he either lacks the commitment or the imagination to actually make it so. While that probably positions him as the living embodiment of DC in the direct marketplace, it’s still (a) a god-damned shame, and (b) renders FLASHPOINT’s subtext just as meaningless as its text. It’s just another thing to keep you amused while you’re reading it.

JOG: Ah, but of course! The heroes zapped away the embodiment of ‘doing it wrong,’ so now revivals can be demonstrably ‘done right!’ In the end it serves the status quo as implicitly correct, although I maintain there’s a special juice to FLASHPOINT in that the extent of what the reboot is even glancing at -- ineffective as it might well prove to be -- gives Johns’ crossover thematics a little extra punch from facilitating something bigger than Johns himself and more superficially drastic than prodding the timeline ahead for a year.

ABHAY: I think what I like so much about your reading is how much I'm inherently rooting for the grim-gritty terminus-of-our sins reality to in fact prevail over boring-ass Barry Allen. I'm rooting for more shocks, more blood, more gore, more viscera, more splatter-horror. I want to see Barry Allen get mutilated repeatedly like Kenny from South Park-- because I'm old and bored and it'd be funny to me. Which I suspect is how a not insubstantial amount of the fanbase actually is receiving these comics, at least if the internet reactions I've seen to Aquaman getting his hand ripped off or whatever, if those things form an accurate sample. The idea that the audience can be walked through this gauntlet of bloodshed and gore in order to come out the other end in a "better state"-- like all of DC’s recently announced plans, I just think that sounds very, very optimistic. But only because it’s a mystery to me why FLASHPOINT would possibly serve to lessen or correct the audience's blood-lust rather than to merely temporarily sate it. A mystery that I hope Grouchy-Batman solves by throwing Barry Allen off that one ledge, or by flying Wonder Woman’s invisible jet all up into his ass or something.

I forgot about OMEGA THE UNKNOWN. And ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN, which isn’t really my book but should probably be on my list. ELEKTRA LIVES AGAIN isn’t going on the list, though! Exercise of arbitrary power!

JEFF: Considering ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN isn’t in print as of this writing, I don’t think you have to worry about forgetting about it, Abhay. I mean, since Marvel’s forgotten about it, why shouldn’t you?

For that reason, I’m reluctant to get into the DC and Marvel canon comparison, though, because DC’s continued commitment to (a) their backlist; and (b) a line of creator owned/participation comics has given them a tremendous leg-up to crazy crackhead Marvel in this debate. Marvel really did a lot of great idiosyncratic stuff in the ‘70s (such as Gerber and Skrenes’ OMEGA THE UNKNOWN, without which there’d be no Lethem book) and even after Shooter came in and cleaned house, you’ve got weird stuff on the fringes like STRIKEFORCE MORITURI by Peter B. Gillis, or titles from EPIC like MOONSHADOW, MARSHAL LAW, THE ONE by Rick Veitch, two SAM & MAX books, STARSTRUCK, STRAY TOASTERS, etc., etc. But you wouldn’t know it from talking to the crazy crackhead because they’re too busy trying to sell you this amazing lamp they found on someone’s lawn so they can get their fix.

TUCKER: I sort of dug on the way Thomas Wayne, upon hearing that his son was alive in another version of reality, immediately throws in with this crewcut dickhead whose fingers he just broke. There’s something positively Batmanian about a guy who says “yeah, so how do I annihilate my entire existence, universe, everything et. all so that my son can live to become a psychotically driven vigilante”, especially when the first part of the answer to his question is “make a homemade electric chair and fry Barry Allen like he’s an Alabama fat boy.” Maybe it’s because I grew up reading DC, maybe it’s because the main thing I’ve learned from the last five years of comics is that I fucking loath Barry Allen, maybe it’s because Tim O’Neil is absolutely right, and Death Row Records means more to me than my father’s intermittent affection, but Issue Two of this Comic Book Series was more interesting than Issue One.

CHRIS: I have far too dim a view of Geoff Johns’s abilities of writing and self-reflection to believe that there’s anything deep and meta in FLASHPOINT, so I’ll sidestep that issue. I think the reason fans have such an impulse to Fantasy Edit the DC Universe rather than the Marvel Universe is because DC’s done it so much themselves. I started reading comics around the time of the first Crisis, so my entire reading life has seen DC pull out repeated attempts to edit and retcon their universe into a new shape. In comparison, Marvel’s been pretty steady with having One Universe, occasional One More Days aside. It’s all Fantasy Editing, but making huge reboots/retcons to the DC Universe at least seems like something within the realm of possibility.

I do think you’re shortchanging Marvel in terms of having Great Superhero Stories. The vast majority of the examples for DC fall into the category of them having employed Neil Gaiman, Frank Miller and Alan Moore at the Right Time. And if you expand the definition out to longer runs (like you did mentioning Starman and the mythological pixie of Good Legion of Super Heroes stories) then Marvel has Simonson’s Thor, Milligan and Allred’s X-Statix, Miller’s Daredevil, BORN AGAIN, Morrison’s New X-Men, the aforementioned OMEGA THE UNKNOWN, Bendis and Maleev’s Daredevil, Simonson’s Fantastic Four, Waid and Weiringo’s Fantastic Four, UNSTABLE MOLECULES, DAMAGE CONTROL, Priest’s Black Panther, Fraction/Brubaker’s IRON FIST, Ennis’s Punisher MAX... I am probably being a fanboy here, but I think Hickman’s FF, and Brubaker’s Captain America will end up on this list too. I realize that few if any of these can stand up to comparisons to the monolithic import of WATCHMEN!!! or SANDMAN!!! and you could throw out [insert big DC run here] to counter half of these examples, and you’d be right to say that the vast majority of my examples come from the last decade or so, meaning Marvel Failed from 1961-2001 to achieve these sort of books, and that they’re all too new to really call Great, and whatever. But come on, Black Orchid? Starman, which I adored at the time but is a sprawling 90+ issue mess that crosses over with fucking UNDERWORLD UNLEASHED and GENESIS? If we’re letting Phil Rizzuto into the Hall of Fame, we might as well throw in Ron Santo and Steve Garvey too.

ABHAY: There's a saying that flits through the ether every so often-- Mark Waid circulated it recently, but other people have said it and I don't think it's an uncommon expression: "The audience doesn’t know what it wants. If it knew what it wanted, it wouldn’t be an audience."

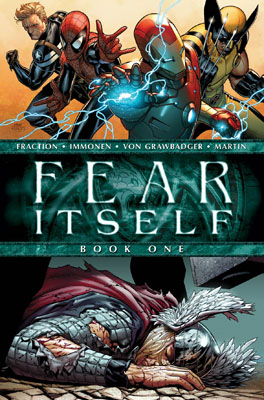

Sometimes I see mainstream fans, in comment sections and such, they say things like "I don't want to read crossovers anymore-- I just want to read good stories about the characters I like." And when I see that kind of talk, I just wonder... do people really still think things can be any other way? I'm a 'sky is falling' type person so I think the ship has sailed. How do you turn back once you've gotten into this incessant cycle of diminishing-returns crossovers? Oh, things broke down for a brief moment when Marvel hit the skids, and they had to bring Quesada & Co. on. For a couple years. But as soon as they saw a hint of daylight, whippity-woo and yee-hah and damn the consequences-- we were right back in it. Now, DC is trying to built this fresh start, but how much do sales have to go down on those 52 new titles before someone with an itchy trigger finger puts out that next Crisis? How can any Crisis be final once you've trained your audience to be on the look-out for the next crisis to upend everything? SIEGE issue #4 was released in May 2010. FEAR ITSELF was announced in December 2010-- they waited seven months. During which time, Marvel released the Shadowland, World War Hulks, Chaos War, and X-Men: Second Coming "mini-crossovers" while their bigger books I think may have been busy teasing the NEXT crossover (they kept teasing some Martian shit...?). If people don't want to be reading crossovers, then based on all of that, is it safe to say they probably shouldn't be reading mainstream comics?

I see people scoff -- scoff!-- that fans only want to read comics that "matter." Of course they do-- that's what they've been taught. What do people think that crossovers wouldn't teach fans lessons in how to best spend their money? The comic audience has been well-trained by comic creators and comic publishers, and yet I feel like the fans are the ones who get blamed when their actions merely reflect that training. "Oh, those horrible old fans who hate change and how they hold us back from creating new things." How did those fans end up that way? Who chased away everyone else? They just point to the fact that no one bought critically-acclaimed book X or no one bought internet-favorite Y, as if the audience had unlimited funds. They keep saying fans vote with their dollars, but ignore that the election’s been rigged.

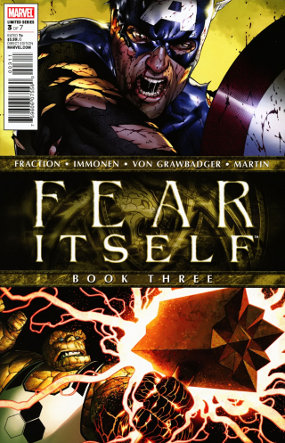

My favorite thing recently: did anybody notice interviews in the promotional campaign for FEAR ITSELF involved Marvel repeatedly telling its fans that there was no such thing as crossover fatigue?! I feel like every interview that I saw, someone would be sure to say at some point that the only crossovers that people are tired of are The Bad Ones. Which-- what's that old expression-- who are you going to believe, me or your lying eyes?

So. Final questions. Are you happy with the current status quo in mainstream comics? Do you think this is all perfectly normal and natural given a more competitive media landscape (i.e. hyping up certain books is simply what is needed to be done given the amount of things competing for readers' attention)? Or are you unhappy but either (a) don't care anymore or (b) never cared really to begin with? If neither (a) nor (b)-- do you think things can actually be any other way, anymore? Do you think things can reverse course somehow and fix themselves, with the current people in charge? Or if there have to be crossovers, if there simply must, is there something you'd like to see them do differently with them than what we've seen so far? Or is Mark Waid right, and you don't even know what you want, and you're waiting for Mark Waid to whisper what you actually want into your ear, late at night, when you were just about to fall asleep? Wait-- how did Mark Waid get into your house? Does he have a key to your house? If he (a) doesn't have a key and (b) the door was locked, did Mark Waid come in through a window? If (a) he is in your bedroom and (b) he has his shirt off, is Mark Waid going through your drawers? Why is he breathing like that? Is he getting ready for a bullfight? If you think Mark Waid is getting ready for a bullfight, is he playing the part of (a) the matador or (b) the bull? On a scale of 1 to 10, how many times will Mark Waid “gore” you? Discuss.

BRIAN: For me, only, I think what the audience “wants” is what we used to have in (say) the 70s or 80s -- smaller lines of books, where “everything counts”, “nothing contradicts other books”, where is issue is (generally) self-contained, giving you at least the feeling of a complete story, but ALSO adds up to “something more” when you read bits of it together, comics that are dense, but not ponderous, and publishing regimes that don’t seem dedicated to thinking “oh, you like that? Well therefore you’ll like three times that THREE TIMES MORE!” Plus, the audience wants to be thrilled and surprised, but not taken drastically out of its comfort zone.

On paper this is very very simple.

I am very much convinced that if the big two superhero universes published roughly half or less of what they do today everything would be much healthier and more focused, and that everything devolves from the insane overproduction we’ve had for many many years now.

I don’t think that the current stewards of the two companies are actually capable of “fixing” things, because I think they’re too beholden to the system that they themselves have created. (dur)

JEFF: “Do people really still think things can be any other way?”

I think the answer is more than likely “no,” of course. Linewide events are these tumors that keep springing up no matter how much everyone talks about cutting them off. They seem like an inevitable consequence of having a shared universe, in a way. Take a shared universe, irradiate it with sustained exposure to editorial mandates and intense bursts of profit and...is it any surprise the fuckers just grow out of control and threaten to take over the entire system? I don’t know what my metaphor for chemo in this case would be, but....no. There will be no ridding ourselves of them.

As for the thing about audiences, you know what it makes me think of? Nirvana. I don’t really know where to go with the song lyrics, but, many years later, the titles stick with me. You know, “Radio Friendly Unit Shifter,” and like that -- I love how Cobain took a bit of shitty radio marketer speak and isolated it. It’s more than just a meta-joke to me, it’s a phrase put in a new and strange light, a military term, like something you’d read in a Burroughs book.

The last few weeks or so, I keep coming back to another song title, though -- ”Pay To Play” -- another term from the music biz (if I’m remembering correctly) for clubs and other venues that make the bands pay an upfront fee to play that venue. I’m not crazy about the song (or “Radio Friendly Unit Shifter,” actually) but I still appreciate how resonant it is. Sometimes, it seems like so much of our culture can be reduced down to that three-word phrase.

The other day, I was talking at the shop with Brian about how typical or atypical a comic book reader I am, and I was of the position that I’m pretty atypical -- I have a strong bond for the characters but don’t care so much for what’s going on with them these days, and I don’t spend a lot of money on them. But Brian insisted I am in fact a pretty typical reader for the industry these days -- a guy who’s almost entirely lapsed as a mainstream comic reader but someone who still pays attention to what’s going on and is either looking for a new way back in to the industry, or a final way out. So it’ll be interesting to see how much of what I write now will resonate with other people reading this.

With mainstream comics these days, I feel more and more like I pay to play. If I want to be able to talk about what others are talking about, I have to read the damn books. And instead of just torrenting them off the net, I either (a) pay to read ‘em; or (b) read ‘em off the shelf at the store and make it a point to buy something else. One of the obvious appeals of a linewide event is the feeling that everything is happening in the same universe, but maybe one of the less obvious appeals is the idea that everyone following different titles in the same universe finally have a common ground. You know, one dude reads Thor, another reads Cap, but theoretically they can both talk about FEAR ITSELF because the same events are unfolding in the shared universe.

It’s the superhero comic equivalent of talking about the weather, I guess. In fact, that’s exactly how the “red skies” worked in CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS—it could be a very minor tie-in (“Hey, look at the sky!”) or it could be something more major—but the idea of giving the fans something to talk about, to “get excited about” was obviously a big deal behind these types of things.

More than anything else, I feel like the pink healthy tissue linewide events metastasize from aren’t the big superhero universes, it’s the desire to talk. You know, “this is the issue that everyone will be talking about!” “This is the event fans will be discussing for decades!” are used for a reason. It’s specifically stated there’s a conversation going on about these books and by purchasing them, it’s implied we have a right to engage in that conversation.

Lemme take this a step further -- we talk about the language of comics or comics as a language, but what if superhero comics are a kind of language? Not like math or something, but...you know how any sufficiently advanced field of knowledge becomes so dense with jargon and specific terminology? What if superhero comics are now not unlike that? We have people who are fluent in the language of superheroes -- not the meta-language of superheroes and not the language used to craft comics, but the actual superhero themselves. By reading superhero comics for a certain period of time, you can become fluent in this language, and then, by reading the characters, you are engaging in a dialogue of sorts with -- I’m not quite sure how to put this, in part because I’m not entirely sure I know what I’m saying -- the superheroes? The universes?

Sure, it sounds crazy but I think this idea of participants in a dialogue has more relevance to serial entertainment than the concept of “the audience” as mentioned by Waid in that interview. (And if I was being a smarty-pants, I would point out that the term “audience” derives from words for “hearing and listening,” specifically, but never mind that.) An audience for a play or an art piece or a book is very different from the audience for a TV show or a comic book because at some point the art piece or the play ends. A TV show or a comic book continues until not enough people are watching anymore -- otherwise, it runs forever. So it makes sense the longer these things run, the more the audience is trained by them, right? I mean, that’s just simple -- if not evolution, than at least education, right? It’s exactly as you say, Abhay: “That’s what they’ve been taught.”

And I think this is a huge fucking problem facing mainstream comics today -- we’ve whittled down our audience to the point where only a (comparatively) small number of people are having that conversation with superhero comics, but they’ve been having that conversation for a very long time. For people like me, it’s been a forty year long dialogue (I’m rounding up a little). There’s an investment in continuing that conversation on the part of the long-time purchaser.

I’m actually okay with that conversation starting over or, you know, having DC or Marvel start another conversation with a new group of people while we continue to have ours over there. But it’s never going to happen that way, is it? There’s not enough money for the companies or for the retailers to stock those books long enough for them to build up a new audience. And the existing group of purchasers will either have no interest in talking to that new line of books (it would be like talking to children, wouldn’t it? There might be a certain charm in the way things are perceived or misunderstood but it seems almost impossible that they could tell you anything you didn’t know.) or they want to talk to it at their own level of complexity (“is there a Barbara Gordon? Is she Batgirl?”). In a very short order, it becomes Ultimate Universe syndrome all over again -- Dazzler is disco, but Ultimate Dazzler is punk! Ultimate Colossus is gay! Is Ultimate Daredevil really blind?

Even if the mainstream comics companies try to start a sustained conversation with a new audience, our audience tends to barge in and dominate the conversation because our audience is *starved* for conversation. It wants to listen to what the companies have to say, and then it wants to say what it thinks about what that company just said.

And, really, the companies are a million times more comfortable talking to our audience because the companies can talk superhero comics at our level. Even if they’re bored by that conversation by now -- really, the only side of our conversation they still care about is the things we tell them with little green slips of paper with dead presidents on them -- it’s easier than teaching the language to a new audience and having to put up with pretty simplistic conversations. People are willing to teach that conversation to, say, a movie audience because there are hundreds of millions of dollars to gain if you succeed and hundreds of millions of dollars to lose if you fail. That conversation gets mapped out a little more carefully, to be sure.

So, yeah. I wasn’t going to buy these comic books but then because I wanted to participate in this conversation, I signed up to talk about them and -- in that weird way I’m doing a terrible job of writing about -- to them? I thought in doing so, I was being motivated by very different reasons than the majority of the audience but now I’m not so sure.

TUCKER: I generally agree with Waid about business-y type stuff, but this is one where I have to part company: super-hero comics don’t have any comparison, because other forms of this kind of entertainment don’t attempt to keep the same audience in the room for this long a period of time. Television shows get cancelled, new things sprout up, the general appeal of certain genres and styles changes generationally--it’s only super-hero comics that posit “keep ‘em in the room, cradle to grave”, and they’ve only been doing that for a few decades now. I don’t disagree that Marvel is telling people they aren’t sick of cross-overs in the hope that those who are sick of them will be further separated from the pack of people who aren’t, that’s a smart (and wholly cynical, also short-sighted) business method that pops up everytime there’s an election, survey, or new product to sell. It’s how independent cartoonists and independent publishers and independent musicians and anything else gets a certain percentage of their support, by strengthening the boundaries between the audience, because audiences like to feel like they’re special and part of groups, especially when dealing with art, where aesthetic decisions have to be made so constantly that the potentiality for feeling stupid and being wrong is at a fevered pitch, even more so when feelings of persecution and shame are tied into the exchange, which of course, they always will be when you’re dealing with something that appeals to infinitesimal audience numbers, no matter how hard people adopt the character traits of Warren Ellis and present them as their own personalities.

That doesn’t really answer Abhay’s question, but generally speaking, I don’t know that Abhay’s question is something I can answer, because I believer there’s a fundamental implication to the question that I don’t agree with, which is that there’s-someone-at-the-helm-making-a-choice, and I don’t think that’s the case. Super-hero comic companies and creators are RE-active forces, they’re not PRO-active. They don’t come up with ideas a year out, or two, and anyone who says different has been proven over and over again to be lying. They flood the market with shitty tie-ins because the week before they didn’t flood it with shitty tie-ins and the numbers went down, so maybe this will make the numbers go up. They kill the Human Torch and see a spike in their quarterly financials, so the decision gets made that they’ll kill characters before each quarterly financial. I can’t use my third grade understanding of economics and supply and demand and business on companies that change their mind every two weeks, and doing so would drive me up the wall and make me even crankier than I already am.

CHRIS: I lived through the period where Bob Harras was the Editor in Chief of a company putting out almost uniformly bad comics once. I will live through that period again. I still like superheroes, and superhero universes, and have come to accept that they’re going to give characters I’m fond of to creators I can’t stand, have Grant Morrison scripts drawn by lousy artists, have Keith Giffen and Marcos Martin draw lousy scripts, see promising books driven into the ground by crossovers and event blitzes, hear the lamentations of their women, etc. I’m also used to television shows I love being cancelled, bands I love die in obscurity. What I Want -- and I like to think I know What I Want -- just isn’t what the publishers Think I Want, and it’s often not what all of the other fans Think They Want, or even what the other fans Actually Want.

On a day-to-day, grousing with friends about the latest press release level, I think about this, and it annoys me. But I can compartmentalize all that shit long enough to enjoy the superhero comics from the Big Two I enjoy. I don’t really know what else to say, I don’t work in any aspect of the publishing or retail side of Comics so I don’t have a horse in the race like lots of other pundits do.

JOG: It’s funny you should phrase the question like this, in such inevitable terms, although, y’know - you’re probably right. And yet, I think right now we’re on the brink of one of those few points where serious change is a real possibility for one of the prominent superhero publishers. Like, I don’t think there’s any greater symbolism out there in the genre right now than the cover artwork of all these DC comics getting obscured by a big GREEN LANTERN banner ad and their innards being disrupted by a promotional comic for SUPER 8. And, you know, not that I’m complaining about Tommy Lee Edwards popping up out of nowhere, but - well...

I saw SUPER 8 this weekend. At risk of sounding precious, it was an efficient, irregularly effective piece of crowd-pleasing craftsmanship that left me feeling as if Joel Courtney and Elle Fanning were walking me through the subconscious ruins of culture like the angels at the end of BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ and nothing good would ever happen again. Because this is J.J. Abrams’ third film as a director, and his first ‘original’ creation in the director’s seat, filling up what’s looking more and more like the obligatory seasonal solo spot for a non-franchise concept in big budget popular genre film-making, and - it actually is essentially a franchise piece. First there was a MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE movie, then a STAR TREK movie, and now a STEVEN SPIELBERG movie, taking the very notion of paying homage to an influential predecessor and executing it in much the same manner as ‘rebooting’ a past-effective bit of property, specifically the ‘70s/early ‘80s Spielberg through roughly THE GOONIES (which he produced), plus some giant monster suspense mechanics derived from JURASSIC PARK, because who can ignore that, right?

What’s interesting, and I think depressing, is that Abrams’ approach -- abetted by Spielberg himself as producer, mind you -- assiduously avoids any of the especially rough patches of Spielberg-the-brand, knowing instead when to swap in some complimentary Michael Bay-isms with that absurd exploding train and its seventeen consecutive volleys of whooshing debris and erupting fireballs that each and every member of the young cast manages to dodge in nimble order. Spielberg-as-director-at-the-time had his action, yes, but just the other day my younger brother was telling me about seeing E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL for the first time in a long while and being kind of startled by that weird, aggressive, scary-funny scene where the government people are charging into the house in contamination outfits and covering everything in white - this really vivid, kind of satiric ‘70s-bred don’t-trust-the-government stuff that Spielberg, a father of the summer blockbuster but autodidactic in that way, would typically drop in, and still does - I mean, I do think I recall the guy quoting IRREVERSIBLE(!!) in the early panicked car ride in WAR OF THE WORLDS, and while everyone on the internet seems to hate the invincible fridge in INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL, it’s still surrounded by this pretty funny and striking sequence with the facade ‘50s town sitting uselessly and melting down under nuclear force.

AH, but wait, wait - RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK was a crucial predecessor of this geeky patchwork cinema style, right? Totally right, but the subtext of RAIDERS was always that Indy was in command of the subtleties of the items he pursues, the dusty matinee serial discoveries that are the basis of his being - that’s how the villains always die in that franchise, they kill themselves fucking around with the magic doodad because they’re not understanding, and Indy is. This, arguably, is a consistent theme in the Spielberg movies Abrams is invoking: understanding something greater than yourself, be it through physical contact with the aliens in CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND or the relationship between the boy and the creature in E.T.

(Uh, SPOILERS for the next paragraph!)

In SUPER 8, there’s none of that. Quite the opposite! It’s established that the alien is trapped on Earth from the machinations of the (of course!) sinister and rather under-characterized government goons -- politically unspecified to function most efficiently as blunt trope -- but it’s made equally ‘clear’ (if only through the screenplay’s fuzziness on the point) that the alien’s psychic connection with various humans is tenuous and futile. Fuck getting to know people - the alien has no qualms against eating random citizens despite its notional mental connection with them as thinking, living beings, much as the movie, in macro, has no qualms about killing assorted standby characters to make the creature seem just a bit more deadly. It’s a very intentional disconnect - the most emotion Abrams can muster in this area is when the boy speaks to the alien underground, and even there it’s left ambiguous whether the alien even understood his words become a plot point literally clatters to life off-screen. And in the end the creature just takes off, taking Joel Courtney’s attachment to his dead parent with him, and leaving everybody to their own devices. There’s no cosmic understanding, no great revelation, no touching of the fingers a la Michelangelo - it’s just a lot of dazed staring at a lens flare receding endlessly to the heavens without you or your memory.

The implications are clear to me - there is no use in understanding what’s greater than you, just navigating in its shadow. You can only ever react to what’s bound to happen. Maybe a pretty girl will hold your hand in the end. Is J.J. Abrams the boy? Is Stephen Spielberg the alien? Can I be the girl? Is Mark Waid the bull, or can he only ever be a matador, dodging out the way of expectations?

And, you know - maybe superhero comics are already like that. There’s evidence! Revisiting old concepts, quoting old stories, spinning it all around and around; if we’re bled ‘till we’re dry by movies, we can’t very well fucking say we didn’t invite it, eh? But GREEN LANTERN - that’s some toxic fucking buzz, man. I think this might be the designated hate object of the season, it looks weird enough -- like an unholy $300 million variant on Guillermo del Toro’s HELLBOY movies -- and it’s usually the odd-looking ones that get smacked around; the genre-as-movies is maybe too formulaic now for semi-odd-ish stuff not to stick out as undesirable while still being close enough to the mold to attract all the seething resentment superhero movies are building, because I think by and large they’re a pretty conservative thing.

I mean, I’m not saying the DC reboot is necessarily going to turn the place into a license farm for multimedia exploitation, even more so than it already is, to the point where stories are poised mainly to reassemble past elements in as schematic a narrative manner as possible (er, more so than it already does) - speaking pragmatically, I’m not sure how they could foolproof that down through the editorial structure.

BUT - I do think the notion of simplifying the superhero genre in a flattened shared-universe space carries with it as much risk for dulling as it does for innovation. For example: how many creator-owned series are going to exist in the new DC? That’s been a quiet area of the conversation; I guess the bigger sellers will continue, but it really does look like that anything that can’t efficiently be pounded into the “superhero” brand is no longer even as ‘welcome’ as it might have arguably been before. I hope I’m misinformed!

Even speaking of the particulars of the superhero genre, the odd stuff, the sometimes-appealing content that crops up, almost on its own volition - the stuff some of us seem to enjoy about FLASHPOINT: that’s not what the movie on the banner obscuring the art is all about. What superheroes do for movies is provide a ready-made means of applying recognizable and/or ready-to-franchise content applicable to established action movie formulae, basically. A little more comedy can seep in, a little more romance, but that’s true for most ‘summer’ action pictures. This isn’t what makes superhero comics interesting to me, albeit to the small extent I still read them. Maybe I’m guilty of valuing the stuff of specialization - more people are going to see a movie right? Yet that’s the hazard, because when someone decides that nobody likes superheroes anymore, it’s gonna hurt in the publishing arm, and hurt there is gonna flow into comic book stores, which is still a terrific thing, a great potential for harnessing the breadth of a wonderful art.

Of course, the revolutionaries in the crowd will say that’s the moment of real change, the only one superheroes can even hypothetically provoke anymore.

So, uh...

To answer your question, Abhay - I don’t think things will have to be quite the way they are in the near-future. And I hope we don’t come to wish they still were.

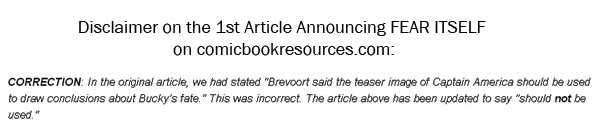

![An image of Iron Man, Steve Rogers and Thor from FEAR ITSELF #1. Quote from a recent interview with FEAR ITSELF's author promoting FEAR ITSELF #4: The scene next month [in FEAR ITSELF #4]... It's the first time that Iron Man and Steve Rogers and Thor have been in the same room in the series.](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/58c6f8b33a041115fb6baf1d/599ccf4de5a68b350fcf931a/599cd9cce5a68b350fd0e5ac/1503451596268/bakers-dozen.jpg?format=original)