Favorites: Black Hole

/![]() Hi folks! I've decided I'll use my slot as a Savage Critic to talk about my favorite comics of all time. I'm kicking things off with Charles Burns's Black Hole--which, coincidentally, Dick Hyacinth had also chosen to use as the inaugural book for his series on the best comics of the decade. So Dick and I will be tag-teaming on this one: I'm going first, then he'll post his thoughts without reading mine, then we'll check out what the other guy has to say and post responses. Should be a pip. Meanwhile, I've also dug a review of the book I wrote for the geek-culture iteration of Giant magazine out of the archives and posted it on my blog--check it out. And now, without further ado...

Hi folks! I've decided I'll use my slot as a Savage Critic to talk about my favorite comics of all time. I'm kicking things off with Charles Burns's Black Hole--which, coincidentally, Dick Hyacinth had also chosen to use as the inaugural book for his series on the best comics of the decade. So Dick and I will be tag-teaming on this one: I'm going first, then he'll post his thoughts without reading mine, then we'll check out what the other guy has to say and post responses. Should be a pip. Meanwhile, I've also dug a review of the book I wrote for the geek-culture iteration of Giant magazine out of the archives and posted it on my blog--check it out. And now, without further ado...

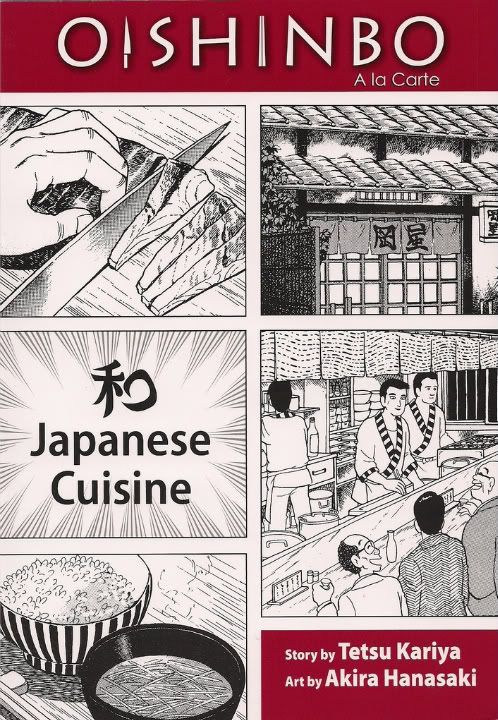

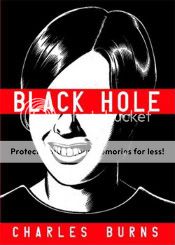

Black Hole

Charles Burns, writer/artist

Pantheon, 2005

368 pages

$18.95, softcover

EXCELLENT

Black Hole

Charles Burns, writer/artist

Pantheon, 2005

368 pages

$18.95, softcover

EXCELLENT

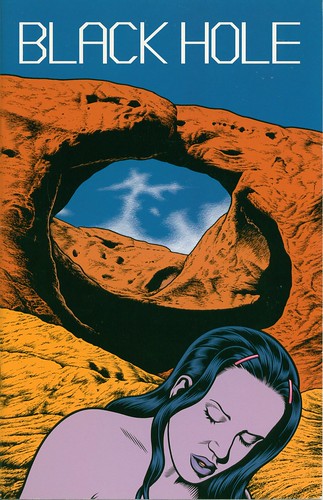

You lose a lot of extremely impressive supplemental material if you purchase or read only the collected edition of Black Hole rather than the individual issues from Fantagraphics (and, earlier, Kitchen Sink). The full-color front and back covers for each issue are probably what stand out in most people's minds, followed perhaps by the almost masochistically detailed endpage spreads, and last but not least those terrific ripped-from-the-hotbox dialogue snippets that accompany Burns's yearbook-portrait openers. I think everyone is probably partial to the one where a guy asks to be cremated if he dies so that his friends can smoke his ashes, but the one from the first issue isn't some nugget of stoner wisdom, it's the premise of the entire book:

It was like a horrible game of tag...It took a while, but they finally figured out it was some kind of new disease that only affected teenagers. They called it the "teen plague" or "the bug" and there were all kinds of unpredictable symptoms...For some it wasn't too bad - a few bumps, maybe an ugly rash...Others turned into monsters or grew new body parts...But the symptoms didn't matter...Once you were tagged, you were "it" forever.

That quote made it into the collected edition as the back-cover blurb. This one, from the twelfth and final issue, didn't:

It's like tryin' to explain sex to a nun - there's no way you'd ever understand it unless you lived it. I was there, okay? Half my fuckin' friends died out there, man. I never dreamed I'd get out of that shit-hole...but one day I notice the stuff on my face is starting to heal and a couple of months later, I'm totally fuckin' clean...out walking around with all the normal assholes.

This directly contradicts the quote from the first issue and upends the premise it establishes. Turns out the horror of the teen plague is finite. Turns out everything that happened in the book didn't need to happen, not the way it did, not based on the assumption that nothing was going to change and they'd never get better. Turns out, in other words, that the teen plague was ultimately like being a teenager itself: It sucks, but you grow out of it.

Rereading Black Hole for the fourth time or so, it's easy to see the set-up for this punchline. Keith in the woods during the kegger where he finds out Chris has the bug, peeing on a tree and grumbling to himself, "This is it...this is all it's ever gonna be. It'll never get better...I'll always be like this..." Chris's similarly themed rebuke of her parents: "You don't understand! You'll never understand! Never!" The constant hyperbole the kids use to describe virtually everything even potentially enjoyable: "It was going to be the best day of my life"; "Rob had brought along all kinds of incredible things to eat...black olives, an avocado, french bred, salami, cheese..."; "All right! That's gonna blow your fuckin' mind!"; "It's called Monument Valley--you won't believe how amazing it is!"; and my favorite, "I want to show you how to make the best sandwich in the world." Chris telling Rob "I'll love you forever, no matter what," and Keith and Eliza telling each other the same thing. Chris's repeated refrain "I'd stay here forever if I could"--in Rob's arms, in the icy water looking up at the night sky. Everything is either the best it can possibly be or the worst it can possibly be, and it will never change.

Needless to say that's just about the most accurate depiction of the emotional life of teenagers I've ever seen. It's how I remember high school. It's not terribly far removed from how I remember college. (And to be perfectly honest, when I think of how I look at the world even now, it's within spitting distance of how I live today, which is probably a big part of why this is one of my favorite comics.) But of course, things do change. Bad things usually get better, which is why it's such a goddamn tragedy any time a teenager commits suicide because of a bad grade or a breakup--or when a group of sick kids feels it necessary to drop out of school, run away from home, and in the case of some characters literally throw their lives away. And unfortunately, good things often get worse; parents do understand, at least some of the time, and it's damn hard to tell someone "I'll love you forever, no matter what" and mean it, and two stoners driving across country probably won't be able to find a cozy apartment where he can make an honest living and she can work on her art and they both live happily ever after. That's a tragedy too.

So why remove the quote that points this out, the quote that completes the metaphor? Maybe--and I'm just guessing here; I've interviewed Charles Burns about this book a couple of times but I don't recall asking him about this--he didn't want to give us that escape valve. Maybe he doesn't want us to read this and think, "Silly kids, if only they knew." Maybe he wants to eliminate anything that lessens the number-one effect of the story and the art here: claustrophobia.

Honestly, the claustrophobia of Black Hole is what struck me the most in this reread. Take the panel gutters, for example. Burns employs a traditional method of delineating between real-time action and dreams or flashbacks--straight gutters for the real stuff, wavy gutters for the reveries. But those wavy gutters still create as uniform a grid as ones drawn with a ruler would. Instead of dreaminess, they evoke haziness, like heat waves radiating up from a road or the room spinning when you're cataclysmically wasted. Indeed, the few times the grids do deviate from the norm is when the characters are completely blotto, or completely panicked--even there, panels remain locked in tiers, and the effect is like careening from one side to another when you're too drunk to stand up straight and really, really wish you were suddenly sober again but you're stuck drunk. There's no way out.

Then there's the look of the art itself. Elsewhere I've described it as like immersing yourself in a blacklight poster, which is apt not just because of the subject matter (look and you'll see a few such posters on a few walls, in fact) but because looking at this book can practically give you a contact high. While I read the book this time around, I thought it might be neat to listen to a couple of playlists I recently made of the kind of electronic music I listened to in college, a time when presence of the kind of emotions you find in Black Hole still feels fresh to me, a time when I got stoned pretty frequently listening to that very music. Even though I did this on the commuter train out of New York, I'll be damned if I didn't feel the pressure on my eyeballs, the weight in my limbs, a slight throbbing of the vision when staring at Burns's flawless blacks and the trademark shine effect of his characters' hair. For the first time in his career, I think, style and substance lined up perfectly. It's not for nothing, though, that the use of drugs and alcohol in the book almost always reduces the options available to the characters--most of the time they prevent people from doing what needs to be done or saying what needs to be said, and even during the story's few positive depictions of inebriation, intoxicants are used to push things toward a preordained conclusion rather than open up other possibilities. No minds are expanded.

Maybe the most powerful aspect of the book's claustrophobic effect is its eroticism. True to adolescent love and lust, the desire these characters have to fuck one another is irresistible and all-consuming--it has to be, or else the story couldn't have happened, and virtually every major plot development wouldn't have taken place either. Frequently the very environments where the sex takes place contribute to this feeling. Rob and Chris's fateful liaison takes place in a graveyard. Keith first sees Eliza, nude from the waist down, under the harsh and unforgiving glare of florescent kitchen lights. He first becomes aroused by her when her tail struggles against the restraint of her towel. Their romance is kindled in her bedroom, surrounded by hundreds of her bizarre (and very blacklight) drawings. They first have sex while stoned as fuck, a red scarf draped over the lamp and bathing everything in crimson. The atmosphere is oppressive, but so can be the feeling of being very, very turned on. "That's all it took to get me totally sexed up and crazy," says Keith of his first kiss with Eliza. "I could hardly catch my breath." (Is it worth noting I knew a girl who looked a bit like Eliza back in college? Probably.)

One final motif comes to mind when I think of how Black Hole works to confine and oppress: repetition. I've already mentioned some of the repeated dialogue, and there are any number of repeated visual cues--shattered glass, snakes, holes--and even repeated scenes--Chris floating in the water, those dream sequences. But there are two instances of repetition that stand out to me the most. The first is when Keith angrily leaves his parents' house to avoid watching some lame TV movie with them, only to end up tripping on acid and watching the very same movie at his friend's girlfriend's place. The second, and the most chilling, is Eliza's sexual assault, which is an implied echo of never-directly-described abuse she suffered at the hands of her stepfather--and, as her nightmare at the end of the book indicates, will likely continue to haunt her dreaming and waking life. Even her and Keith's blissful roadtrip escape is just a tour of places she's already been, trying to recapture the happiness she knew long ago. And maybe this more than anything else is why cutting that final reveal that the bug was temporary was the right move: Bad things usually get better, but that doesn't mean they never come back--different, perhaps, but the same in all the ways that count. Sometimes you can break free of something only to spin right back around to it, spiraling inward into that gravitational maw until that bad thing might as well be constant, for all you can truly escape from it.

I mean, the book is called Black Hole.

Hi, I'm Dick, and I'm really excited about being here since this is one of the first comics blogs I remember reading obsessively (two of the others were Fanboy Rampage and Jog the Blog, so TRIPLE excitement, actually). It really is a great privilege to write on the same site as those folks you see on the sidebar. And now that I have this forum, I can devote

Hi, I'm Dick, and I'm really excited about being here since this is one of the first comics blogs I remember reading obsessively (two of the others were Fanboy Rampage and Jog the Blog, so TRIPLE excitement, actually). It really is a great privilege to write on the same site as those folks you see on the sidebar. And now that I have this forum, I can devote