Three Bloody Ones: This week in superhero decadence.

/![]() Dark Reign: Zodiac #2 (of 3):

Dark Reign: Zodiac #2 (of 3):

Superhero decadence! I love it! You love it! Do you love it? Do you love me? I love you! Even though I disappear for weeks at a time doesn't mean you aren't always in my heart! I've gotta follow my bliss, babe! Gimme a kiss. Right up to the monitor. Your boss isn't watching. Or your spouse, housemate. Whatever! Where was I? Right: superhero decadence. Some say all the shared-universe cape comics are decadent, in that they're made self-absorbed, genre-absorbed from the rigors of the shared universe, the frequent crossovers. Others identify it as superhero comics with a lot of bloody violence, and often some gross sex but never with much nudity, because that's dirty. Or maybe it's more of a designation of an era than a type of genre work - these are the days of decadence, like a society primed to collapse from its idle care and disparity. It's not 'decadence' in the proper literary sense, but then superhero comics have rarely been considered proper literature.

(mosaic provided in-comic, true believer!)

(mosaic provided in-comic, true believer!)

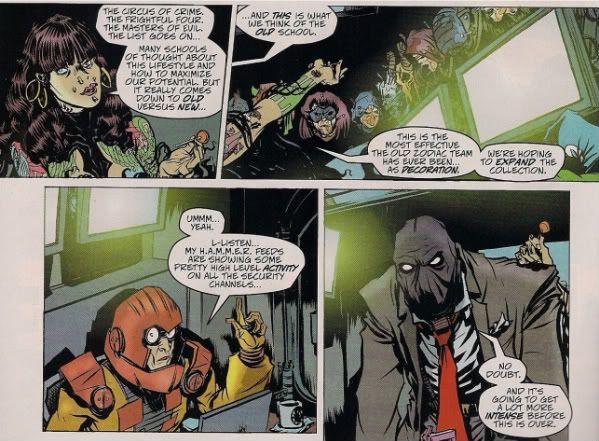

Maybe we just need a GOOD comic to poke through as a handy aid. And you can hardly get more acutely self-referential than a three-issue Dark Reign series dedicated to reviving a supervillain team that Wikipedia tells me has undergone four prior incarnations since 1970, the most recent hailing from 2007. Writer Joe Casey does the honors, and, on first blush, it doesn't seem like a very deep concept results. A callow young man calls himself Zodiac, dresses in a suit and puts a bag over his head, and goes around recruiting D-list or relatives-of-supervillain allies, basically for the purposes of killing the shit out of loads of people and beating up the Human Torch.

But that's not all that's happening. Casey isn't just indulging his affection for wayward super-concepts -- Whirlwind! The Circus of Crime! -- but providing a platform on which marginal bad guys can be defined philosphically. Really! The 'plot' of this book is thin so as to become secondary; what's more important is the purpose of Zodiac's mission, to establish forgotten supervillains as agents of the irrational in face of the muted villainy and conspiratorial motives of the Norman Osborn as Director of National Security concept. Indeed, the series isn't so much part of a larger story as a pocket of resistance in which seemingly inapplicable characters take on necessarily reactionary roles.

And if Zodiac's take on life seems reminiscent of a certain grinning agent of chaos as depicted in a certain recent not-from-Marvel blockbuster superhero movie, it's nonetheless interesting as directly applicable to the 'real world problems, kinda' stance of so many Marvel events. Why so serious?

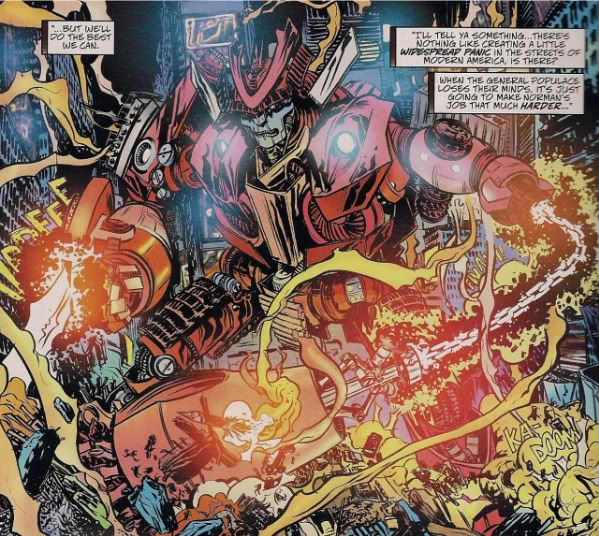

Mayhem ensues, crucially as drawn by Nathan Fox in a style that may seem heavily reminiscent of Paul Pope's -- and the presence of frequent Pope colorist José Villarrubia helps that right along -- but works just as well to marry wrinkled, stylized human figures to some old-fashioned Marvel kick. I can't say the storytelling is always as clean as it could be, but the feeling is always visceral, and that's necessary to keep Casey's story from seeming academic. The words might tell us about why Zodiac is faking a new arrival of Galactus -- for the hell of it, to cause trouble, to force the institutional villains to lose their shit coping with something as irrational as a purple guy from space that eats planets -- but the pictures carry the enjoyment, the sick thrills of being horrible.

They blow up a hospital at one point. It's mostly superheroes that survive. "Well, that's all part of the dance, isn't it?" replies Zodiac. He knows superheroes aren't going to die (or stay dead if they do). He knows the contours of the world. But in his headquarters, decorated with the mounted heads of all prior Zodiac members -- that's decadence! -- he still plans a means of taking on the status quo, which itself is a challenge against the favored ways of writing supervillain characters in the crowded universe. Old ideas, new contexts. Call it an essay story, as much as Warren Ellis' & Marek Oleksicki's Frankenstein's Womb from Avatar this week, a walking tour of modernity's precognition.

This, on the other hand, is an imagining of super-stories. Aren't they all?

The Boys #33:

Yet superhero decadence needn't be restricted to shared-universe stuff. Now, you might be thinking this particular series is a satire, I know, but really it's as on-the-ground as your typical genre piece. That's where it functions best.

The Boys, you see, takes place in a world where all superhero metaphors are made literal. So, when a patriotic superhero appears, ostensibly to remind us of the appeal of martial-themed characters, he's literally presented as having fought in a war on behalf of the United States. Except, he hasn't, since superheroes are typically full of shit in this Garth Ennis-written place. And indeed, superheroes didn't really fight in WWII, the obvious point of reference -- they're not real, after all -- so the bloody punishment handed down to the character gets that extra whiff of righteousness.

And taken on its face, this is very shallow commentary, ignoring, say, the appeal of superhero characters to servicemen in WWII, possibly the all-time high of superhero popularity, to say nothing of the subversion of the patriotic trope in god knows how many prior, less mouthy superhero comics from decades back. All the shading, then, is added by the comment's positioning in the comic's 'world,' where the whole idea of heroism has been essentially co-opted by corporate-political interests, in the form of corporate superheroes. From that angle, we can see that the contemporary idea of the throwback patriot superhero is presented as inherently propagandist, divorced from a genuine wartime conflict and thereby toxic in its nostaliga for killing. It also helps to know that the primary two fighters of the superhero-slappin' cast of the Boys have different opinions on 'supes,' which form an internal conflict on Ennis' part in regards to the subject matter.

Oh, and it's way funnier if you're reading this stuff right now, in the pamphlets, with all of these unfortunately placed Project Superpowers house ads chock-full of glowing Alex Ross images of the greatest generation of superhumans. Yikes!

Anyway, it's also worth mentioning that this commentary is only part of the issue, which mainly builds up to next issue's finale of the current 'superheroes fight back' storyline, while nudging the various subplots forward a bit. Those vary a lot in quality: the bits with lead supe the Homelander growing tired of corporate constraints are pretty good, particularly if you're reading the series in conjunction with its current spin-off miniseries, Herogasm - the effect is basically having the series go bi-weekly, with the stories jumping back and forth in time; it's clearly been planned to work out this way, since events in one title seem to correspond with what's going on in the other without giving away too much information. Meanwhile, the continuing exploitation of good girl superheroine Starlight leans weakly on routines about skimpy costumes and superhero storytelling attitudes toward rape (conclusion: they're gross).

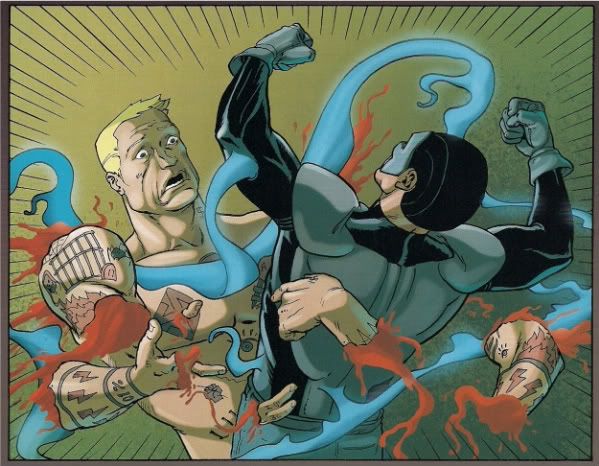

More immediately, you'll notice the fill-in artists now have fill-ins of their own, with Herogasm's John McCrea & Keith Burns flown in to replace Carlos Ezquerra, himself filling in for cover-credited co-creator Darick Robertson. Ironically, this makes the series seem all the more like a real superhero comic of today, planting it in the nitty-gritty of ongoing genre work. I actually like the McCrea/Burns work this issue; Ezquerra (who just did fine work with Ennis in The Tankies) didn't seem to mesh well with the series' disposition, while these artists are with it enough to draw anti-hero Butcher exactly like Frank Castle in certain panels (see above), preserving a little of the old all-Ennis concordance. OKAY, as it tends to be.

Absolution #1 (of 6):

On the other hand, some comics just don't warrant a lot of attention. Writer Christos Gage, while previously experienced in film and television scripting -- I've only seen director Larry Clark's 2002 made-for-cable Teenage Caveman, which I remember liking -- first came to the attention of a lot of comics readers through his 2007 revival of an old Wildstorm property, Stormwatch: P.H.D. This is an original work, published by Avatar, but it still feels like a revival, specifically that of a Marvel MAX-type work from 2003 or thereabouts. I'm talking straight-shot hard 'R' superhero stuff, directly crossed with some other genre that might withstand spandex trappings.

Here that other genre gets especially specific: the cop drama wherein some particular cop has crossed the line and started doling out justice outside the system. Superheroes are usually outside the system, granted, so Gage posits a world where superheroes are essentially a special police division, possessed of fantasy powers yet restricted by many of the same basic rules of conduct and procedure; it's almost a one-for-one swap of 'cops' for 'superheroes' in the plot, with gory throwdowns in place of shootouts. All the while, our John Dusk is haunted by visions of the many atrocities he's seen men commit, a bit like Rorschach's cracking up as stretched to scenario-length.

It's all played out exactly as you'd expect so far -- Dusk even has a non-super detective girlfriend who just might be catching on to his killings -- with almost no distinguishing characteristics. In fact, almost nothing even happens in this issue that wasn't already established in the 11-page issue #0 from a while back, save for the introduction of a few nondescript superhero teammates and the suggestion that Dusk's oozing, quick-hardening blue mist abilities might be starting to lash out as much from his subconscious desires as anything else.

The art is by Roberto Viacava, whose character designs fall somewhere in between Paul Duffield and Jacen Burrows in the Avatar cartoon continuum; colorist Andres Mossa gives some of it a decent sun-faded candy coat, but he can't help the stiffness of a lot of the action or the cast's general inexpression when not confronted with imminent violence. As a whole it fits in that it's as bland as everything else, down to Our Man stumbling into a blood-spattered rape chamber in which the monster in charge was nonetheless thoughtful enough to drape a blanket over the breasts of the victim in the immediate foreground. Now there's superhero decadence like we all can recognize. AWFUL.