My Life is Choked with Comics #20 (Ver. 2.0): Captain Hadacol

/![]() This is a song about Louisiana and some of the people in it. Or outside it. Or nearly anywhere in these United States as the 1950s approached, and superheroes declined as charismatic rogues stood tall, proud like they knew we'd miss them once fatedly laid low. It's a nostalgic record.

This is a song about Louisiana and some of the people in it. Or outside it. Or nearly anywhere in these United States as the 1950s approached, and superheroes declined as charismatic rogues stood tall, proud like they knew we'd miss them once fatedly laid low. It's a nostalgic record.

Let it play. Can I offer you a drink?

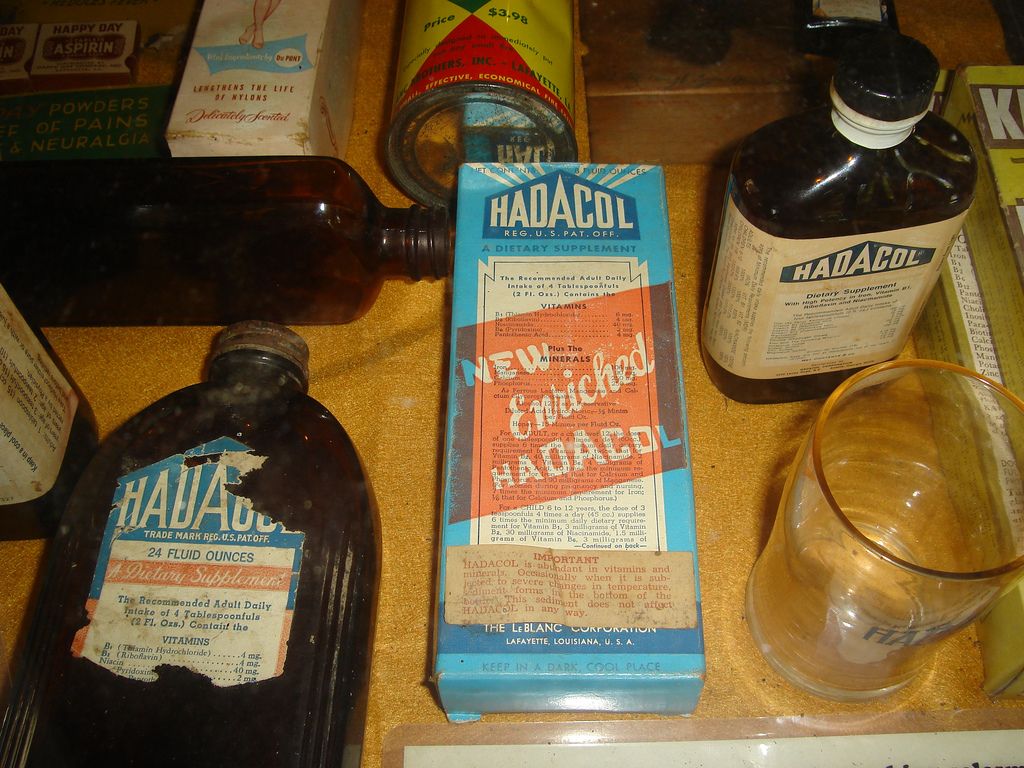

This is Hadacol.

***

Twelve Percent True

(Being a second and updated version of a post of January 31, 2010, amended to include exciting superhero art and duly expanded/adjusted text and formatting.)

(Being a second and updated version of a post of January 31, 2010, amended to include exciting superhero art and duly expanded/adjusted text and formatting.)

***

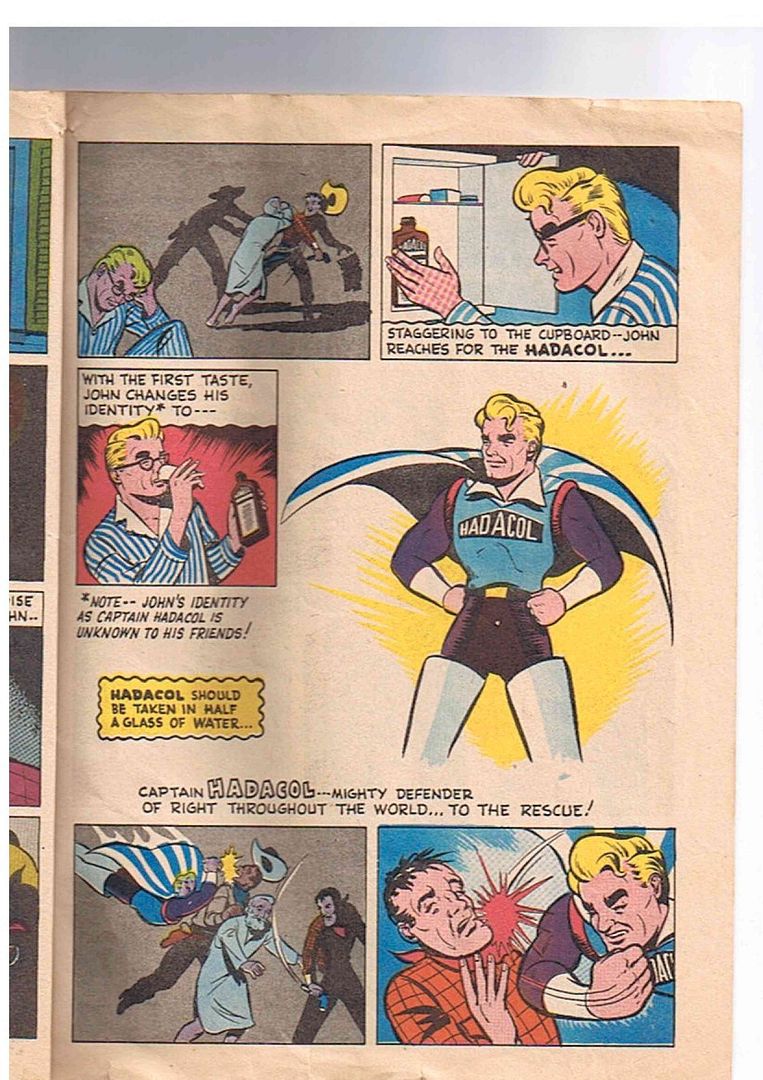

Hadacol was a popular 'patent medicine' of the late 1940s that transformed into a full-blown national fad as the century's midpoint arrived. "A Dietary Supplement," as you can see, Hadacol was supposed to be taken four times per day -- once after every meal, then right before bed -- as diluted in water, half a glass for one tablespoon. A typical bottle retailed for $1.25 (over $11.00 today), chock-full of vitamins B1, B2, and B6, with Niacinamide, Iron, Manganese, Calcium, Phosphorous, and sweet sweet honey.

And... diluted acid hydrochloric, which the product's Wikipedia page happily informs us (without citation) was intended to open the body's arteries to facilitate better absorption of the Hadacol health mix, including its 'preservative' - 12% alcohol, roughly as much as in a typical bottle of table wine.

By literally every account I can track down, Hadacol was absolutely disgusting, which probably didn't matter: it was healthy! Sort of! At least, enough so to circumvent the legal/moral/religious concerns of 'dry' communities across the land, while giving even the most saturated household a special license for consumption. Plus, it was fun, the ballyhoo of it all, much grander than that behind the boozy potions of earlier American miracle vendors, dating back to before the Revolutionary War. A new, modern, post-WWII country needed a contemporary elixir, and Hadacol cured just what ailed 'em.

Dr. James Harvey Young provided a detailed overview of the Hadacol phenomenon in his 1966 book The Medical Messiahs: A Social History of Health Quackery in Twentieth-Century America (rev. 1990, free online), so I'll just run down the highlights. Hadacol was the brainchild of one Dudley J. LeBlanc, a Louisiana politician, entrepreneur, and quintessential Colorful Character from Down South prone to boasting that he got the inspiration for his bottled success in 1943 by way of swiping an injectable prototype from out of a doctor's office after the nurse had left the room. It wasn't LeBlanc's first patent medicine endeavor; one earlier project, Happy Day Headache Powders, in fact ran afoul of the Food and Drug Administration. Apparently not one to lay down and accept defeat, LeBlanc compressed the name of his former Happy Day Company into Ha-Da-Co-L, the 'L' being his own last name.

But if this time it was personal, LeBlanc didn't show it - mostly, he liked to say that he hadda call his product something.

I bet that's not the first time you've heard that joke. Hell, it's not even the first time today if you listened to that song like I asked you. But don't go thinking the lore of Hadacol entered into song and jest unassisted - it's said that LeBlanc himself commissioned Everybody Loves That Hadacol, licentious subtext and over-the-top claims and all. I mean, did that guy grow new toes?! Hadacol sounds scary.

Did the song end? Here, try this.

LeBlanc started out hawking Hadacol in French to Louisiana's Cajun population, to which he belonged, but it didn't take many years for the earthy nostrum to build its way up to the level of a genuine south-to-midwest consumer craze, aggravated by aggressive advertising tactics and lavish spending prompted by the possibility of tax write-offs. Mad culmination manifested in 1950, in the form of the Hadacol Caravan, a massive traveling spectacle accessible to the consumer only with the presentation of two Hadacol box tops (one for kids). Plenty more would be available inside, as the caravan wasn't a particularly new idea - it was a medicine show, of a type rapidly withdrawing into antiquity. Leblanc's affair was way bigger and far more monied than avarage, but it was essentially traditional, and I can't imagine some happy Hadacol purchasers didn't grasp the implication as to the, er, palliative qualities of the medicine accordant to such shows.

Ann Anderson's 2000 study Snake Oil, Hustlers and Hambones: The American Medicine Show positions the Hadacol Caravan as effectively the last great example of its folk entertainment kind, though poorer docs continued to wander into the 1960s. The form went out with a bang: among the Caravan's features, albeit not at the same time, were Hank Williams, Roy Acuff, George Burns & Gracie Allen, Jack Dempsey, Jack Benny, Sharkey Bonano's Dixieland Band, Bob Hope, Carmen Miranda, Dorothy Lamour, Rudy Vallée, Cesar Romero, Mickey Rooney, Milton Berle, Jimmy Durante, a chorus line, clowns, acrobats, vaudevillians, beauty queens, prizes, fireworks, and, of course, LeBlanc himself, cruising up through the venue in a white Cadillac. While he was serving in the Louisiana state senate, mind you. By the show's 1951 season, audiences ballooned to number in the tens of thousands.

Interestingly, Anderson's description of the show's over-the-top disposition -- purportedly adorned with unsubtle nods toward the star concoction's primary ingredient and winks at an aphrodisiac quality -- falls right in line with the awfully tongue-in-cheek tenor of the extended jingles we've already heard. Writer Jeremy Alford's account is similar, presenting some of the Caravan's action as approaching a prolonged and elaborate in-joke between Dudley J. LeBlanc and interested personages in Dry America:

A clown dressed in a police uniform stumbles around on stage and makes his way into the audience. A spotlight follows the ensuing folly as every time the clown takes an energetic step, an oversized bottle of Hadacol nearly jumps out of his pocket. He reaches quickly for the tonic and helps himself to a healthy swig. His massive glasses glow in the evening shade with each pull on the bottle. It's obvious that this is one drunken clown, and he's soon joined by another inebriated fellow whose nose lights up when he takes sips. The crowd ' children and adults ' loves it and screams into the night air.

Now, make no mistake, this is hardly the first instance of 20th century advertising adopting a fairly sardonic posture in re: the product at hand. Witness this 1932 marvel, fronted by a pair of New York City brothers that everybody reading this site has heard of:

And that's for Oldsmobile, as opposed to the most noxious libation this side of Jeppson's Malört. Yet people often still think of mid-century advertising as goofily forthright in its glosses and fibs, even while the Fleischers long ago poked at the virile promise of automobile ownership, and LeBlanc, decades later, sometimes giggled openly at the carnival pitchman's shamelessness of his own endeavor; this was a man with the trickster's spirit enough to stand on stage with an inter-party political rival and, at one point, switch his address to French so as to excoriate the man next to him to the delight of fluent attendees, as the target smiled.

Needless to say, he also got into comics publishing.

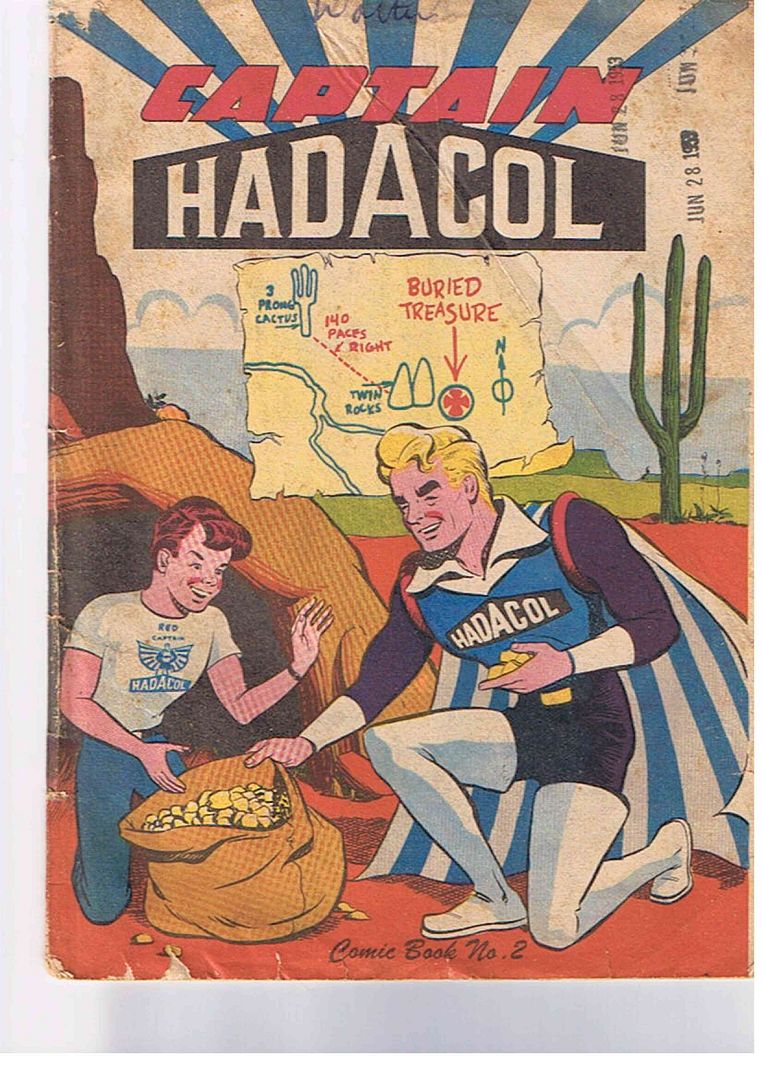

One comic, as far as I know. A superhero comic.

About a superhero that gets his powers from an authentic, eminently purchasable health product of dubious medicinal value, 24 proof.

That treasure took seventeen hours to find, because Captain Hadacol is smashed. And that's because the secret to his powers is booze. VITAMIN BOOZE.

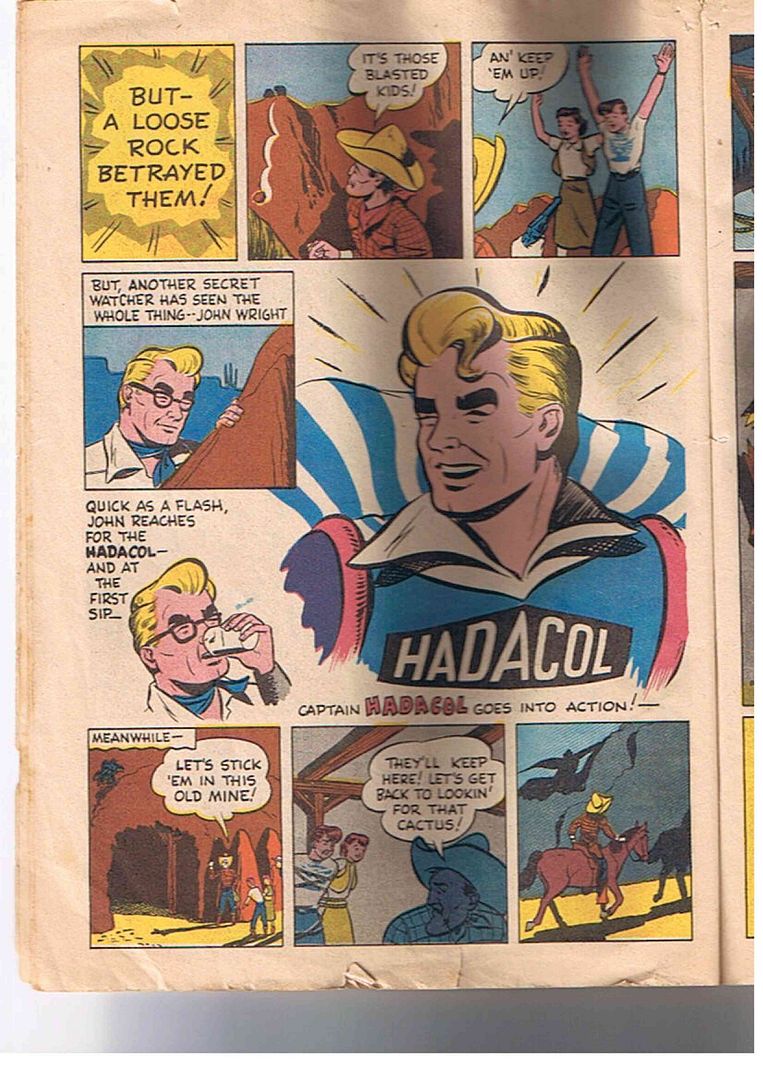

I don't actually own this comic, nor do I know who wrote or drew it. All scans to follow come courtesy of the Deborah LeBlanc Collection, which informed me that Captain Hadacol -- whom I'd only known of by barest reference in product lore -- is a Superman-Popeye hybrid character, a plain man granted enormous temporary powers through imbibing the sponsor potion (available now, just $1.50). This came as a relief, since Cap looks strikingly like a 'vitamin'-addled normal guy who perhaps only thinks he has powers. Also, his costume looks like stuff he found. Then again, it probably does take a hero to successfully navigate in over-the-knee flat boots; I hope Marvel is taking notice for its upcoming Heroic Age, 'cause those Napoleonic puppies are back in style.

Just look at that wholesome, concerned face, bedecked with the same deadly squint promotions connoisseur Chris Ware sometimes uses for his Super-Man, which puts me in dire fear for Twelve Percent Lad's health. I just made up a superhero name right there; the proper name of that boy on the cover is "Red Reddie," whose family appears to have some firm connection to "John," the top-secret bespectacled identity of Captain Hadacol. "Comic Book No. 2" sees the Reddie family and their blond chum cutting loose down on the ranch:

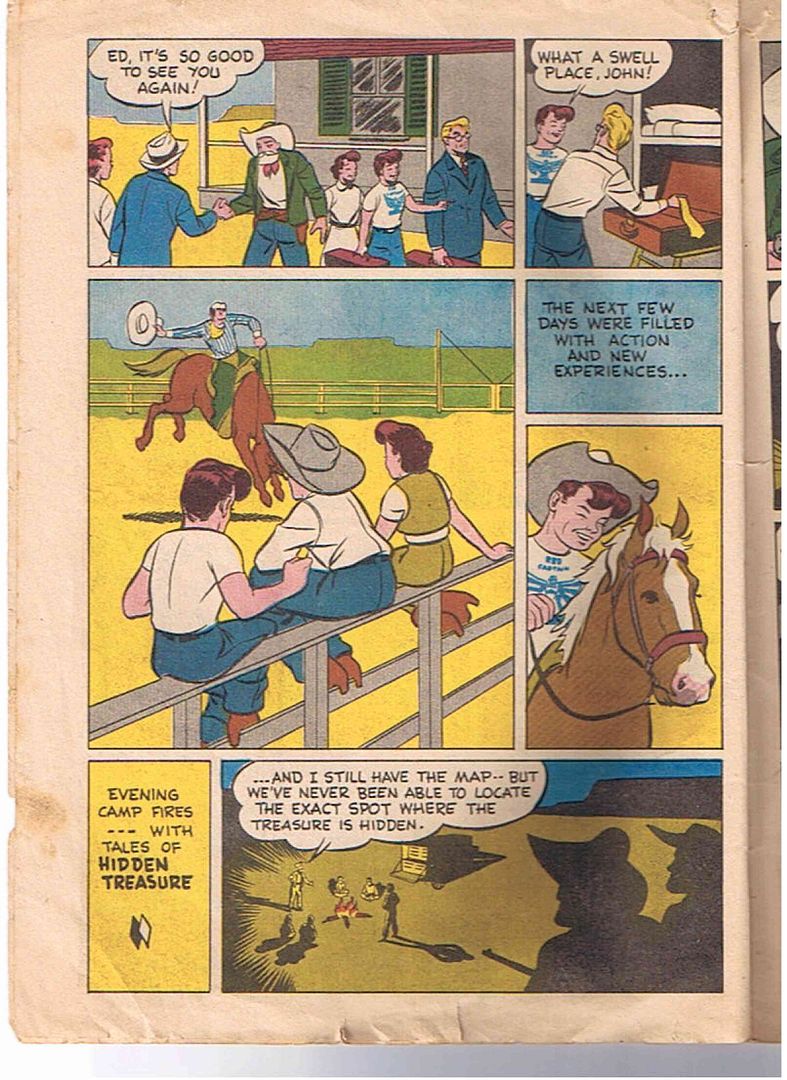

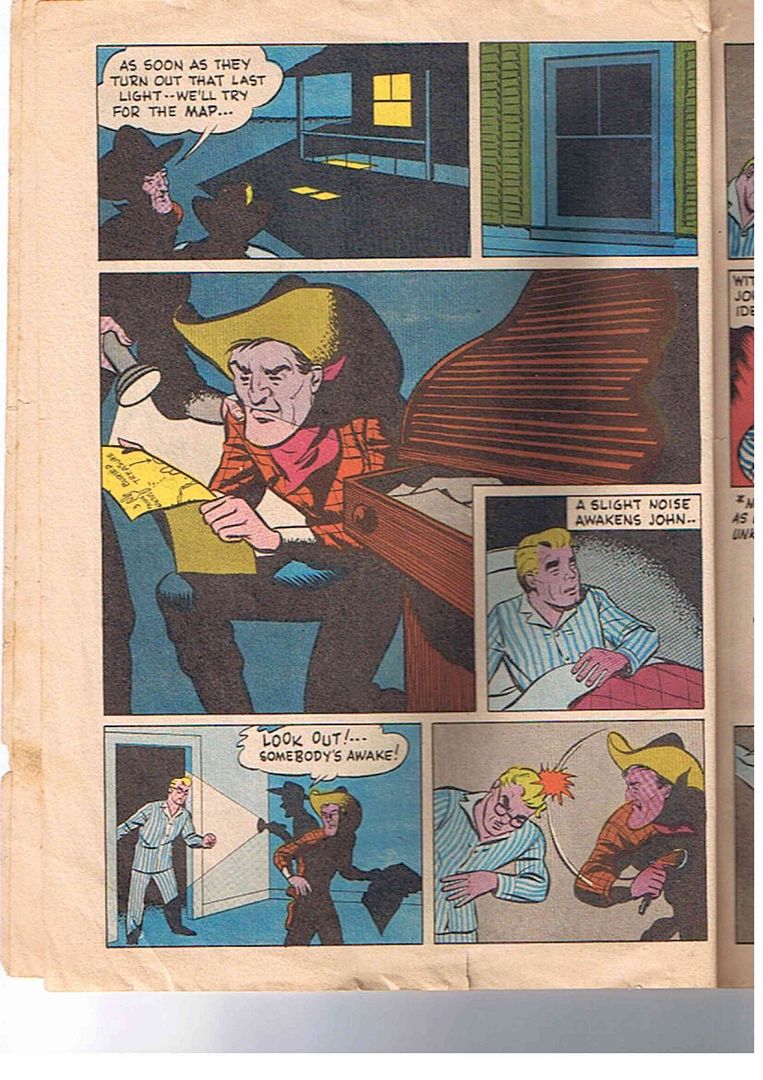

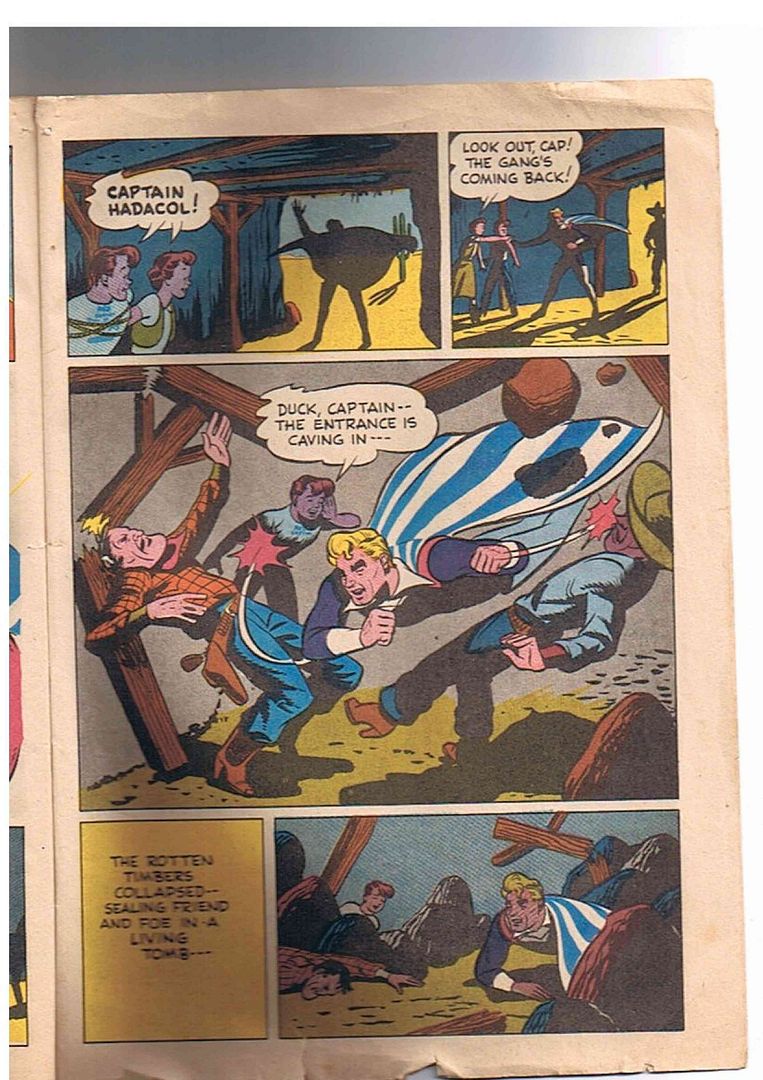

Now if you're like me, your first thought is "gee, nice colors!" It's not unlike the anonymous, popping fresh style that does a lot to compliment Fletcher Hanks' (earlier) work. But the more you get into this comic, the more you notice its odd stylistic tics, like how four out of its nine story pages utilize the same motif of an expanded center panel, bordered on one side with a smaller column of panels and capped top and bottom with two thinner panel rows. Two additional pages utilize an even wider midsection, giving the comic an eccentric expanding and contracting feel.

Then there's the in-panel art, prone to a curvy sort of caricature, with scenery elements that border on the expressionistic - dig that wiggly drawer balancing the composition! Anyone who knows me is fully aware that I'm the worst person at spotting Golden Age art in the whole of North America's comics readership, so maybe this is some phenomenally well-known talent cashing a Hadacol check anonymously, but it's also possible that a local illustration hand put this thing together in the spirit of just having a go at the form.

Use as directed, kids! Actually, Anderson's book describes a totally different Captain Hadacol -- possibly the contents of the otherwise elusive issue #1 -- in which Our Man entreats a boy to slam eight consecutive bottles of Hadacol for immediate super-strength. "The alcohol in eight bottles of Hadacol equaled a pint of bonded whiskey," Anderson notes. And while that's coincidentally where my powers come from, apparently in this issue the power of Hadacol has expanded sufficiently to charge a man up 'by the label,' in addition to changing his clothes, thereby suggesting a brand of humor doubtlessly better suited to the Hadacol Caravan.

Here's another iteration of Artist X's layout style, with the interrupted big panel now up top. You're not missing any story reading along in this abridged manner, by the way; it's a totally uninspired genre short, propulsive mainly from its heavy breathing page compositions. Quite a thing for shadows too.

I mean, wow - Captain Hadacol's ready to kick some ass up there! I pretty much came out of this story hoping that nobody else discovers the secret of Hadacol, given what it does.

So, in that apparently everyone is a superhero by way of Hadacol's intervention, I can only conclude that the premise is broadly the same as that of The Boys. And sure enough, Captain Hadacol has the same basic superman look as the Homelander -- as well as similar military-corporate interest superheroes from Marshall Law or Power and Glory -- down to that faintly Aryan appearance beloved by talents eager to tease Fascist implications from superhero characters, as it takes only a few modifications to go from flat boots to jackboots.

Captain Hadacol isn't a fascist, of course; indeed, while I may be stretching, there's perhaps an interesting ethnic specificity to his costume, its cape seemingly patterned after the blue and white of the Hadacol box, but its overall blue, white and red-striped color scheme, with a single point of gold in the belt buckle, very loosely approximating the colors on the flag of Acadia, from where the Cajun people came (this is not to be confused with the present, similarly-colored Louisiana-specific Acadianan flag, which was not designed until 1965). Given that the costume itself appears to be slipped over a normal dress shirt and slacks, I wonder if Captain Hadacol 'himself' didn't make any promotional appearances at local events?

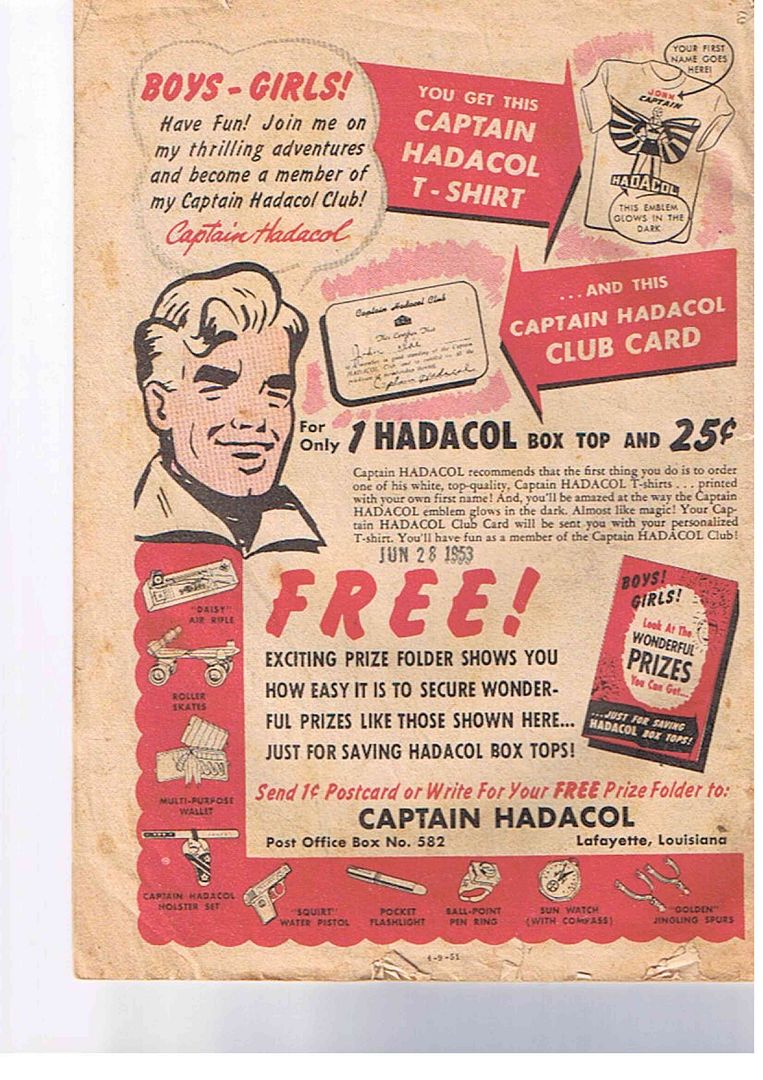

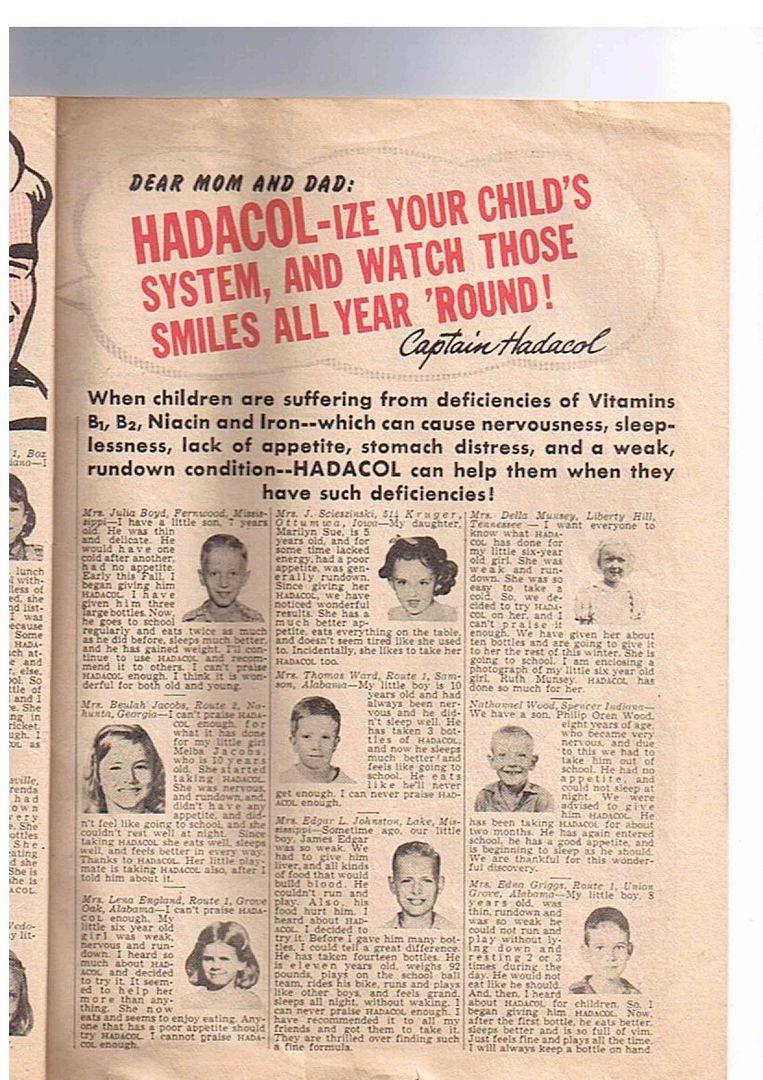

This is the back of the comic, listing the real treasures boys and girls can discover with Hadacol's aid; this whole 'comic' 'story' business is plainly secondary. In teeny tiny type at the bottom, it also lists a possible date of publication, January of 1951, right at the roaring height of the craze. We can therefore accept Captain Hadacol as exactly the kind of thing all those crafty satiric superheroes comment on, selling stuff to the public out from the seat of authority -- perverse, corrupt ideas of 'heroism' or 'justice' to Pat Mills or Garth Ennis, rather than decorous booze -- though most of us know that superheroes weren't really so idealistic at birth, certainly not the murderous ones sprung from the pulp tradition (say, Batman).

Still, comics are older than superheroes, just as medicine shows were older than Dudley J. LeBlanc. The most recent (39th) Overstreet guide contains no mention of Captain Hadacol -- given that the issue at hand is #2, there was presumably at least a #1, unless LeBlanc was pulling the contemporaneous comic book stunt of starting a run at a higher number to create the illusion of demand for nonexistent early issues -- although its lovely Promotional Comics section does mention that comics relating to patent medicine date back into the mid-19th century, much like the American medicine show, a fellow promotional entertainment. The two are thereby historically linked.

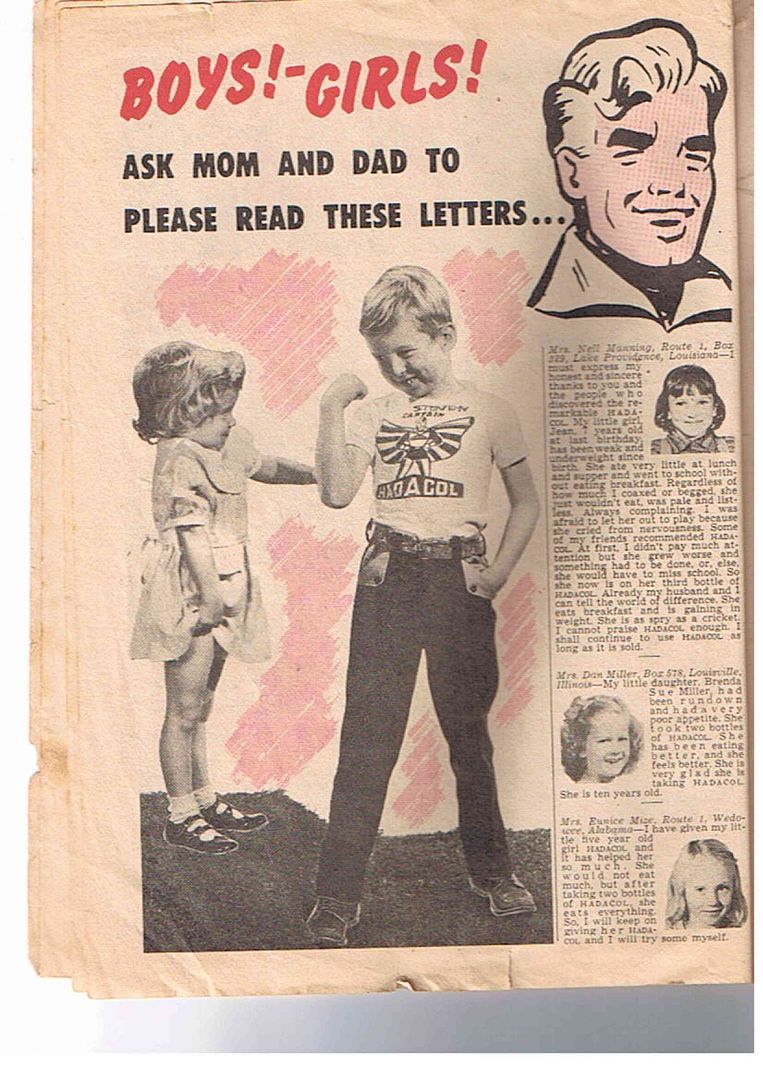

Yet look at the differences! If the Hadacol Caravan -- at least from the scattered historical record available to me -- seemed awfully wry and rightly sophisticated in its rib-poking promotion, Captain Hadacol the comic occupies a promotional area where LeBlanc wasn't kidding around - the comic book form manifested a simple entertainment for kiddies, if potentially enlivened by oddly emphatic art, and ideally facilitated forthright appeals to Mom and Dad. Behold:

It'd probably be in the Hadacol spirit to make a beer muscles joke here, but instead I'll observe that the promotional comic, as opposed to the promotional live jamboree, operates on these pages as appropriate for a naïve form. As the song goes:

my ex she lives near Bayou Blue

and she could not read or write

she just reads comic funny books

every day and every night

but then she took some Hadacol

and it gave her quite a thrill

'cause now she's teaching high school

she's the best in Abbeville

-from Everybody Loves That Hadacol (Cajun Version), as posted above

Ha, you see? Comics are stupid! Adults who read them are STUPID! They're for little kids, everyone knows this, you can reference it in a song and everyone will get the joke! That's why it's the perfect means for kids to deliver these urgent testimonials to their parents - how could a dumb, childish art form like this lie? It's on-the-nose advertising, and in an inappropriate venue for the arguably more mature posture of the more colorful Hadacol hype. In case you can't see the small text:

--

I must express my honest and sincere thanks to you and the people who discovered the remarkable HADACOL. My little girl, Jean, 7 years old at last birthday, has been weak and underweight since birth. She ate very little at lunch and supper and went to school without eating breakfast. Regardless of how much I coaxed or begged, she just wouldn't eat, was pale and listless. Always complaining, I was afraid to let her out to play because she cried from nervousness. Some of my friends recommended HADACOL. At first, I didn't pay much attention but she grew worse and something had to be done, or, else, she would have to miss school. So she now is on her third bottle of HADACOL. Already my husband and I can tell the world of difference. She eats breakfast and is gaining in weight. She is as spry as a cricket. I cannot praise HADACOL enough. I shall continue to use HADACOL as long as it is sold.

--

My little daughter, Brenda Sue Miller, had been rundown and had a very poor appetite. She took two bottles of HADACOL. She has been eating better, and she feels better. She is very glad she is taking HADACOL. She is ten years old.

--

I have given my little five year old girl HADACOL and it has helped her so much. She would not eat much, but after taking two bottles of HADACOL, she eats everything. So, I will keep on giving her HADACOL and I will try some myself.

--

And, you know, comic books were immature at that time, though superheroes were rapidly hibernating by 1951, in favor of crime and (increasingly) horror comics. And Disney comics and Archie comics, yes, but the nasty stuff caught the attention of society's guardians, terribly concerned for the well-being of susceptible youth.

No worries of this sort from Dudley J. LeBlanc - like Wu-Tang, nearly half a century later, Hadacol is for the children:

--

I have a little son, 7 years old. He was thin and delicate. He would have one cold after another, had no appetite. Early this Fall, I began giving him HADACOL. I have given him three large bottles. Now, he goes to school regularly and eats twice as much as he did before, sleeps much better, and he has gained weight. I'll continue to use HADACOL and recommend it to others. I can't praise HADACOL enough. I think it is wonderful for both young and old.

--

I can't praise HADACOL enough, for what it has done for my little girl Melba Jacobs, who is 10 years old. She started taking HADACOL. She was nervous, and rundown, and, didn't have any appetite, and didn't feel like going to school, and she couldn't rest well at night. Since taking HADACOL she eats well, sleeps well, and feels better in every way. Thanks to HADACOL. Her little playmate is taking HADACOL also, after I told him about it.

--

I can't praise HADACOL enough. My little six year old girl was weak, nervous and rundown. I heard so much about HADACOL and decided to try it. It seemed to help her more than anything. She now eats and seems to enjoy eating. Anyone that has a poor appetite should try HADACOL. I cannot praise HADACOL enough.

--

My daughter, Marilyn Sue, is 5 years old, and for some time lacked energy, had a poor appetite, was generally rundown. Since giving her HADACOL, we have noticed wonderful results. She has a much better appetite, eats everything on the table, and doesn't seem tired like she used to. Incidentally, she likes to take her HADACOL too.

--

My little boy is 10 years old and had always been nervous and he didn't sleep well. He has taken 3 bottles of HADACOL, and now he sleeps much better and feels like going to school. He eats like he'll never get enough. I can never praise HADACOL enough.

--

Man, this is a lot of testimony! How about another song?

Feel free to do the Hadacol Boogie along at home (or an especially liberal workplace), although I think it might be a euphemism for sex. Hey - where do you think kids come from?

--

Sometime ago, our little boy, James Edgar was so weak. We had to give him liver, and all kinds of food that would build blood. He couldn't run and play. Also, his food hurt him. I heard about HADACOL. I decided to try it. Before I gave him many bottles, I could tell a great difference. He has taken fourteen bottles. He is eleven years old, weighs 92 pounds, plays on the school ball team, rides his bike, runs and plays like other boys, and feels grand, sleeps all night, without waking. I can never praise HADACOL enough. I have recommended it to all my friends and got them to take it. They are thrilled over finding such a fine formula.

--

I want everyone to know what HADACOL has done for my little six-year old girl. She was weak and rundown. She was so easy to take a cold. So, we decided to try HADACOL on her, and I can't praise it enough. We have given her about ten bottles and are going to give it to her the rest of this winter. She is going to school. I am enclosing a photograph of my little six year old girl, Ruth Munsey. HADACOL has done so much for her.

--

We have a son, Philip Oren Wood, eight years of age, who became very nervous, and due to this we had to take him out of school. He had no appetite, and could not sleep at night. We were advised to give him HADACOL. He has been taking HADACOL for about two months. He has again entered school, he has a good appetite, and is beginning to sleep as he should. We are thankful for this wonderful discovery.

--

My little boy, 8 years old, was thin, rundown and was so weak he could not run and play without lying down and resting 2 or 3 times during the day. He would not eat like he should. And, then, I heard about HADACOL for children. So, I began giving him HADACOL. Now, after the first bottle, he eats better, sleeps better and is so full of vim. Just feels fine and plays all the time. I will always keep a bottle on hand.

--

But she wouldn't have much time to do it. In late 1951, LeBlanc sold his interest in Hadacol to investors up north. Six weeks later, they discovered that Hadacol was in fact in tremendous debt, and distribution soon collapsed amid FTC complaints and mounting criticism of the product's unique not-all-that-healthy approach to diatary supplementation. LeBlanc was saddled with a hefty tax bill, and never again realized that level of success; a non-alcoholic vitamin drink, Kary-On, proved unpopular. However, despite unsuccessful bids for the U.S. Congress and the governorship of Louisiana, he remained popular enough in his home district that he died in office as a state senator, 77 years old in 1971.

In 1952, the year after the end of the Caravan and the fall of Hadacol, a comic book titled Mad debuted from the increasingly notorious comics publisher EC. Under founding editor Harvey Kurtzman, it would bring a skeptic's eye to comic books, something typically reserved for newspaper or magazine cartoons, more favored species of the comics form, devoting itself to cracking the codes of superheroes and advertisements and gala shows and everything else Hadacol and LeBlanc profited from, in part through comics itself.

And then in 1954 the Comics Code Authority was formed, and comic books couldn't speak ill of judges.

Oh well, you know - the seed was planted.

As for Captain Hadacol himself, indulge me this advertisement of my own:

***

HELP ME. I AM RUNDOWN AND LACKING IN VIM, AND THE ONLY CURE IS INFORMATION. IF YOU KNOW ANYTHING ABOUT CAPTAIN HADACOL -- WHO WROTE OR DREW IT, HOW MANY ISSUES WERE PUBLISHED, WHERE OR HOW THEY WERE DISTRIBUTED OR SOLD -- PLEASE LEAVE A COMMENT OR SEND ME AN EMAIL.

***

Hell, maybe all my half-formed and tenuous ideas as expressed here will change with a little more Hadacol context. Maybe the discovery of future rip-snortin' Cap'n Hadacol adventures will yet boast a texture unique in promotional funnies; its creator didn't seem the type to leave any ballyhoo hanging in the air without the special grin of a born gamer. But as it stands now, Captain Hadacol is more an oddball exhibit of neat visual qualities speaking to a sophistication that comic books, in their stories and their society, could not embody, and so the joke could only be on them.

Let me sum it all up with a story that appears in nearly every Hadacol-related text, starting with Martin Gardner's 1952 omnibus expose Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science, which I have not read. Accordingly, I'll print the legend.

It so happened that Dudley J. LeBlanc, as Hadacol boomed, was being interviewed by Groucho Marx, whose brother Chico had played/would play the Caravan, which, all things considered, probably provided a nice payday for hard-working performers transitioning away from hot stardom.

At one point, Marx turned to LeBlanc and asked what Hadacol is good for.

"It was good for five and a half million for me last year," LeBlanc replied.

***

- One million thanks to the Deborah LeBlanc Collection for the wonderful scans and information.