My Life is Choked with Comics #18 - King Smurf

/![]() The Politics of Smurfing

The Politics of Smurfing

This is the story of the day the Smurfs became terrorists.

***

***

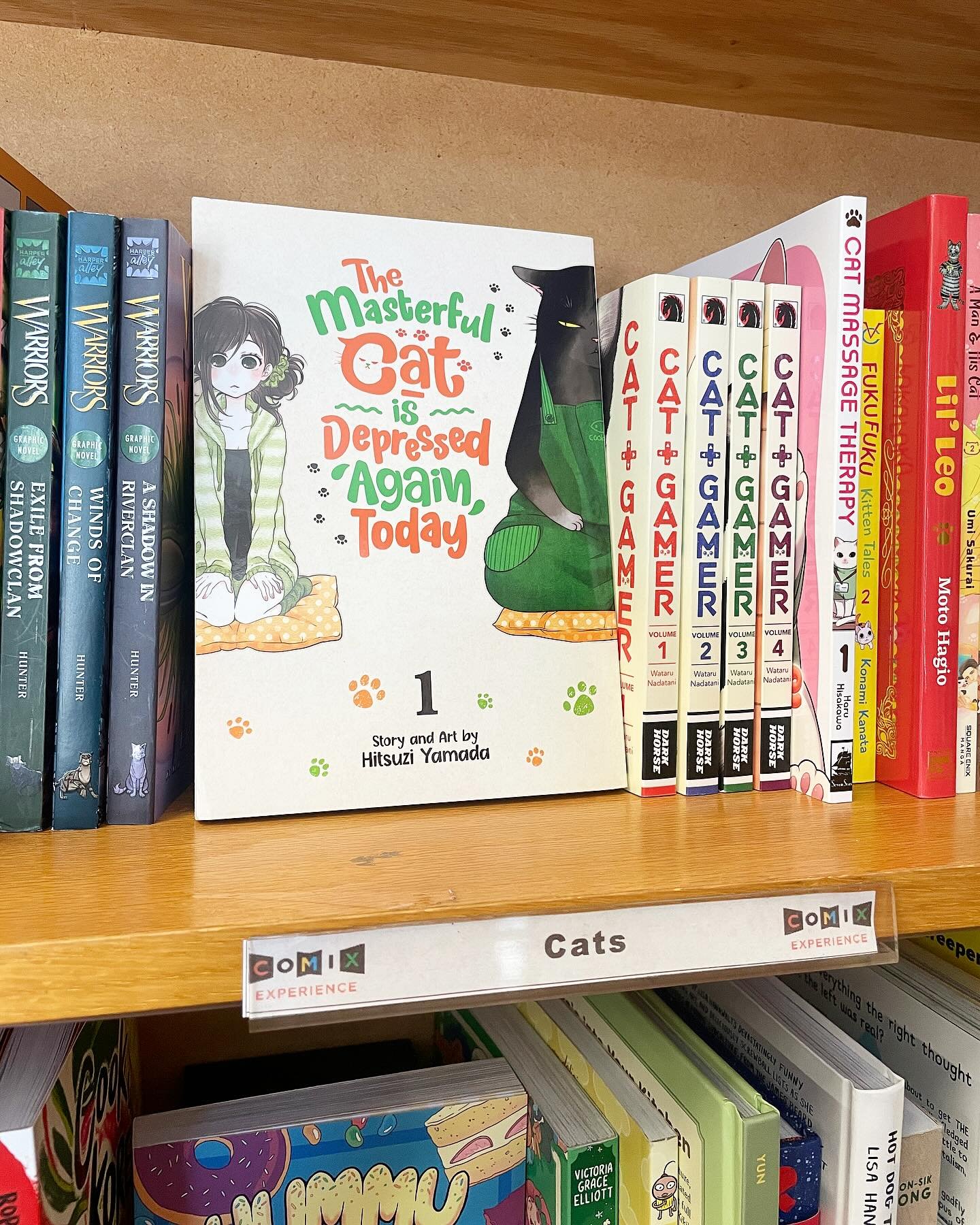

In 1965, the comics album King Smurf (Le Schtroumpfissime) was released to French-reading audiences. It was drawn by 'Peyo' (Pierre Culliford), the artist and animator who had created the Smurfs (Les Schtroumpfs) in 1958 as impish supporting characters for his Johan et Pirlouit medieval adventure series. It was written with Yvan Delporte, editor-in-chief of Le Journal de Spirou, the Belgian comics magazine in which the story had been serialized.

In 1978, the Belgian publisher Dupuis licensed an English translation of the album to Random House -- sans its original back-up story (Schtroumphonie en Ut) -- for simultaneous release in Canada and the United States. As evidenced by the back cover of the U.S. edition, an entire line of English-language Smurfs books had been released (or at least planned) by that time, although the franchise's prolifigate merchandise had only just begun to materialize stateside, its longstanding smash success in Europe not quite yet gone supernova.

In 1981, the animation studio Hanna-Barbera Productions introduced its wildly popular television adaptation of the Smurfs, which ultimately ran for 256 half-hour episodes, until 1990. It was a cultural force. Most of you reading this can still whistle that damned theme song. Yes you can. R1 dvd box sets began appearing in early 2008, although I suspect many viewers were not aware that the little blue characters were approaching their 50th anniversary, or that it all used to be a comic, or that the comic used to be political, sometimes, owing to its time and place.

King Smurf was adapted into an episode of the animated series in its first season. The edges were smoothed down considerably. But then, the Smurf Village is a secret place, and I expect the comic book Smurfs would rather keep a few things to themselves.

***

Our tale begins on a beautiful night in Smurf Village. Papa Smurf, who is totally not a Communist, is up late cooking up some alchemical thing for a no-doubt beneficial purpose.

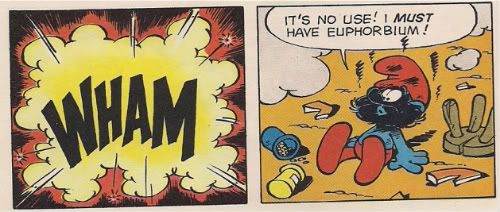

But wait! Papa is fresh out of the suggestively-named herb "Euphorbium," which is crucial to the success of his project! We're never told what exactly Euphorbium does, or how it ran out, but my current theory connects it to the community service obligations that required Papa's appearance in Cartoon All-Stars to the Rescue. Anyway, it's obvious this little ritual to Glycon won't work without it.

I do think the whole explosive materials in the lab deal is what's known as 'the pistol in act one,' just a heads up.

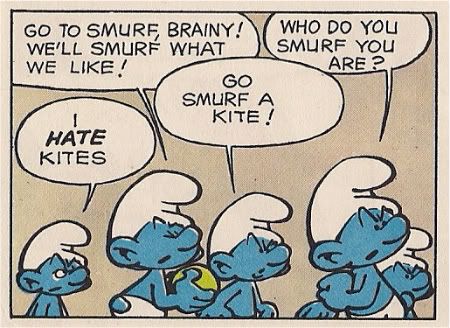

As such, Papa takes off the next morning to fetch some herb on "the other smurf of the mountains," where I presume the police helicopters cannot navigate. He asks his Smurfs to "be very smurf" while he's gone, at which point a Smurf smurfs in to suggest a round of smurf, but then Brainy Smurf smurfs in like a smurfwit and starts demanding everyone work on restoring a bridge and shit (smurf). The gang isn't terribly enthused about addressing Smurf Village's longstanding infrastructure problems.

Oh right, "go to smurf," yeah! Did you think me and your elementary school classmates were the only ones to play the 'replace ass with smurf' game? No, I kind of expect that possibility occurred to Peyo approximately three seconds after he and fellow cartoonist André Franquin came up with the Smurf (Schtroumpf) language over dinner, and may indeed have made up the majority of the Schtroumpf-related interactions for the remainder of the week.

You do know the Smurf language, right? And how the different Smurfs have different characteristics, even though they look pretty much the same? Brainy Smurf is slightly more complicated, in that he's both a brain and a total dipshit who's usually wrong about things. He's actually a really good, funny character in this particular comic, a very specific-seeming caricature of (pseudo)intellectual elites as social conformists, trusting in the status quo to reward them for their blustering support while remaining totally clueless to anything outside of their frame of reference.

Naturally, Brainy expects to be hailed leader of the Smurfs, more or less because he figures it's his turn, just for being as brainy as him. This (again) doesn't go over well with the other Smurfs, who eventually opt for their first-ever display of "universal smurffrage." A few kinks in the plan quickly emerge.

The philosophical profundity in the bottom left corner comes from Grouchy Smurf, who boasts one of the more iconographically questionable origins in comics history, having been a sunny Smurf who was bitten by a bug that turned his skin black and made him violent and sour; more and more Smurfs were bitten and made black, until Papa managed to expunge the blackness from Smurf society, although Grouchy was still grouchy afterwards. This all went down in 1963's The Black Smurfs (Les Schtroumpfs Noirs), not available in English.

Getting back to the story, a lone anonymous Smurf soon arrives at a startling revelation: if he promises people stuff, they'll vote for him! So, when Brainy Smurf finishes boring some other Smurf to tears via assertions of his Papa-approved greatness, Our Smurf zips in and promises to pass a law outlawing bores - success!

Soon Lazy Smurf is promised a Right-Not-to-Work Bill, Harmony Smurf is promised a position as first trumpet in the Big Smurf Band and Vanity Smurf is complimented on his immense physical beauty. Smurf Prime even makes sure to urge Dopey Smurf to vote for Brainy, trusting that he'll somehow screw it up. Speaking of Brainy, the niceties of the political process seem to have escaped him.

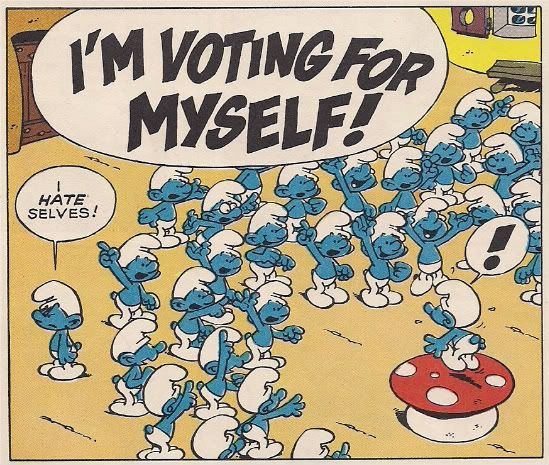

Before long, Smurf (and yes, it's always just VOTE FOR SMURF, since it could be anyone in his position, you see) is having parades in his honor, and delivering hot campaign speeches before inviting the lads out for drinks while Brainy babbles on and on about his status as virtual incumbent to an audience of Grouchy, who hates drinking.

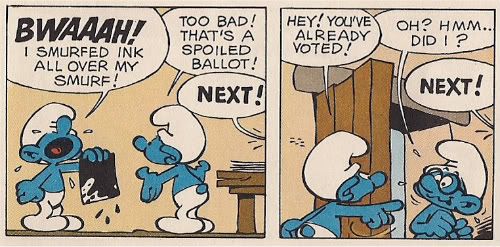

Election day arrives. It's a real nest of vipers, chock-full of thrown-out ballots and rampant fraud; thank heavens there's no appeals in Smurf Village, or we'd still be awaiting the results.

In the end, Smurf-Just-Smurf emerges winner of the farce, with Brainy receiving votes from only himself and Dopey Smurf, who is so phenomenally stupid that he managed to screw up fulfillment of Smurf's intent for him to screw up, paradoxically arriving at the correct result for possibly the first time ever. The total voting population of Smurf Village, by the way, is exactly 100, counting the absentee Papa. I only ask that you dedicate your next trivia night victory to me.

***

If you really want to understand the Smurfs-in-comics, though, just take a look at their feet. Fat, oval lumps, real dinner rolls.

Oh, I'm sure there's some longstanding precident for that look, and it's obviously been used in many places subsequent. But I always associate it with Belgian comics of that period, specifically the tight-knit "Marcinelle school" of Belgian cartooning, named for the town surrounding Dupuis, aesthetically headquartered in the Spirou anthology and bound by blood (and marketing) to always oppose Le Journal de Tintin, home of Hergé and the style that would become known as the ligne claire, the "clear line," after some Dutch guy cooked up a sufficiently catchy name in the '70s.

The Marcinelle school was different, focusing broadly on vigorously cartooned forms and the illusion of movement. Granted, there were several individual departures, including, ironically, the "school's" founder, Joseph "Jijé" Gillain, who eventually developed a distinct oscellation between a clear line-inspired cartoon approach and a polished 'realistic' style, a dichotomy later replicated by his noteworthy pupil, the Frenchman Jean "Moebius" Giraud. But the core identity of the style was nonetheless firm, perfected in the works of André Franquin, the great cartoonist who headed Spirou's flagship series, Spirou et Fantasio, in its mighty golden age.

However, almost nobody in the U.S. has heard of Spirou et/ou Fantasio, whereas everyone over the age of 15 has heard of the Smurfs, and so they are the sealed-in-amber conclusion of the Marcinelle school for many American eyes. And while Peyo was no Franquin, there's something about the uniform chubby roundness of the lil' blue devils that suggests a summary at work, a distillation of accrued cartooning tropes into factory-ready icons, every one perfect, and perfectly ready to adopt specific, isolated attributes: Brainy, Lazy, Grouchy, etc. After all, if you're not going to tend toward realism, as the Tintin school did, you might as well plunge into sheer iconography, the sure symbol of Smurf society.

But that's no secret; it's as plain as your eyes, regardless of your personal awareness as to Papa's seat in Belgian comics history.

No, the mystery is provided by Delporte, who lived until 2007 and wrote a ferocious amount of comics, not to mention his share of scripts for the Smurfs cartoon show. As stated above, though, the Saturday morning iteration tended to be sedate, in spite of the slapstick, while Delporte's Smurf scripts for comics took on an often satirical edge. They were children's comics, sure, but keenly aware of their place in a society owned and operated by adults.

Take, for example, 1973's Smurf Vs. Smurf; I haven't read it (since it's never been translated to English), but Wikipedia's summary suggests that it's a fairly pointed lampoon of the strife between the Dutch-speaking northern region of Belgium (Flanders) and the French-speaking South (Wallonia), as translated to an ongoing Smurf Village argument between the verb-dominant Smurfs (ex: I wanna smurf you like an animal) and their noun-dominant brothers (I wanna fuck you like a smurf). All-out war in the streets soon erupts, leaving Papa to restore peace via the conclusion of the hit comic book and motion picture Watchmen.

I'm serious; the story ends in almost exactly the same general manner as the Alan Moore/Dave Gibbons classic, with Papa fabricating a threat by villain and gourmand Gargamel so as to pretty much scare the warring Smurfs into a state of peace. I sure hope Wikipedia isn't pulling my leg, since there's even apparently an ambiguous ending suggesting that the harmony may be short-lived! No word on whether Grouchy Smurf narrates from a journal kept of the story's events, or if any right-wing publications discover it in the end.

***

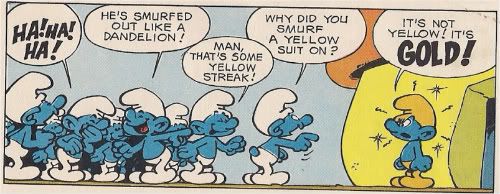

But oh, dear readers, trouble soon arrives in the fair Smurf municipality. The freshly-elected Smurfy Smurf hustles into his room to change into a little something he'd obviously been working on for a while: a brand-new footy pants 'n cap combo, forged from pure gold. Or, colored in that manner, unsuccessfully.

Undeterred, Our Man declares that all shall henceforth refer to him as King Smurf, resulting in highly respectful peals of laughter. No matter: when Harmony Smurf pops into the His Majesty's office to collect on his Big Smurf Band promise, King Smurf gives him a really fancy title (First Chief Head Spokesman), outfits him with a drum, and sends him out to announce that all Smurfs will respect and obey, or face terrible consequences.

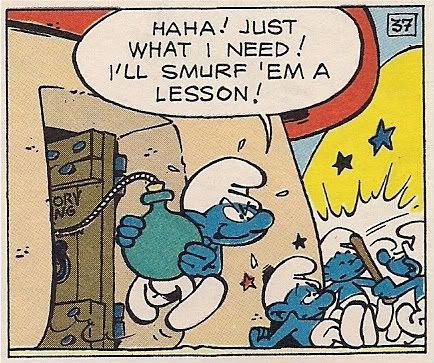

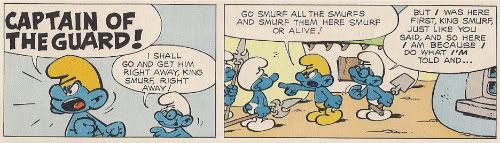

This prompts Hefty Smurf (who is strong) to bust into the King's room to kick his ass. But King Smurf knows what desires lurk in a powerful Smurf's heart.

In mere minutes, Hefty has lined up an honor guard of fellow Smurfs, armed with deadly blades. Brainy can't believe he wasn't picked. Tiring of his shabby digs, King Smurf decides to put the rest of the village to work building him a rightly awesome palace. Sensing another authority figure whom he can leap behind, Brainy takes up his tools while the guards round up the rest of the Smurfs. The reign of terror has begun.

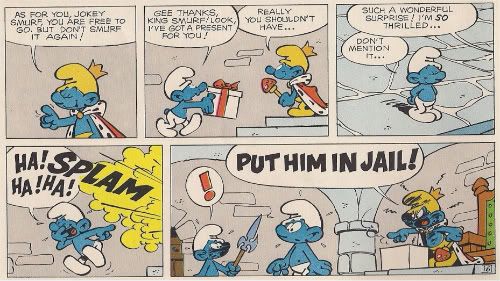

Yes, forced labor is the new rule of the day! Smurfs now live as slaves, worked to the bone under threat of death! The rule of law is useless too, and inequality reigns supreme; poor Jokey Smurf gets hauled before His Eminence for pulling off one of his knee-slapping 'exploding gift' tricks on a guard, and comes face to hideously singed face with the new double standard.

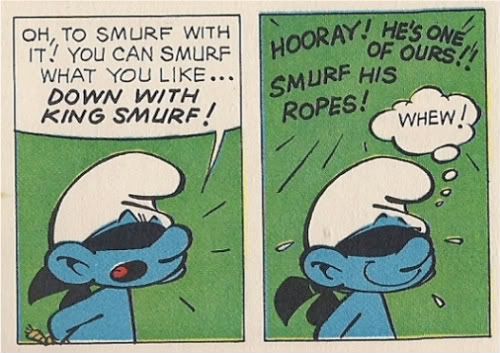

Sending a man to jail for innocently detonating a bomb in someone's face in the name of fun is step #5 or #6 down the road to totalitarianism, as I've personally mentioned to several magisterial district judges, so you can imagine the uproar in the Smurf community following Jokey's arrest and detention. But a march on the palace only leads the Smurfs to be held back at speartip, and the crowd is soon dispersed. Is there no hope left in this town?

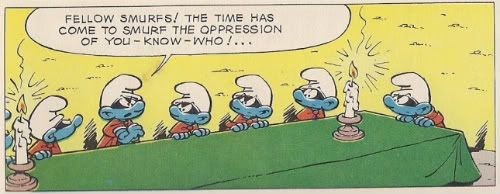

Under the cover of night, a shadow falls across a mushroom house. A cloaked figure evades the evening patrol. He knocks on a door, whispers a password, and enters. Then descends. There's friends waiting, under the earth.

La résistance! De weerstand! A regular White(-Hatted) Brigade! Smurfs should not fear their government - the government should fear its Smurfs!!

No time at all is wasted. The Secret Smurf Society drugs a guard, busts into the prison and runs like hell to the woods beyond the village. Brainy Smurf, no doubt anticipating a change in the winds, happens to be with them, and also manages to be the only one caught. For the remainder of the comic, he'll occasionally get a one-panel cut to his prison cell, in which he'll ponder when his friends will be around to break him out and hail him as a hero. Nobody will ever come.

That's probably the most powerful lesson a young person can take from the Smurfs: don't be an asshole.

***

The politics of King Smurf in particular -- or at least its deep-seated distrust of political mechanisms -- likewise had some probable correlation with the adult life of Belgium surrounding its creation.

After all, both Peyo and Delporte were born in 1928, positioning their individual comings-of-age directly against the German occupation of Belgium during World War II, in which many citizens were shipped away for use as forced labor in the Nazi machine. It's extraordinarily easy to see those rebel Smurfs' covert activities as reminiscent of the many factions of the Belgian resistance, often squirreled away in the woods, spiriting away downed pilots and evading capture to subvert another day.

However, this reading seems insufficient, since neither Belgians nor Smurfs elected Adolph Hitler, who was not specifically a king. No, Belgian had a king of its own, Leopold III, a controversial man in those days of struggle. It had been less than three weeks since the German invasion of May, 1940, when the King of the Belgians announced the nation's surrender, without the approval of the legislature. Compounding the difficulty, Leopold III chose to remain in Belgium under the occupation, while the civil government eventually repositioned itself in London, outside the village of mushrooms, although unsuccessful overtures were made to construct full occupational governance in Belgium.

This resulted in a duly anarchic state of affairs, with the Belgian monarch and legislature-in-exile declining to entirely recognize one another's authority, neither body cooperating with the Nazis and their military government, and various aspects of the resistance -- necessarily separated by language, remember -- sometimes operating to their own ends.

Interestingly, though, from this chaos grew the might of the Marcinelle school, the home of the Smurfs. Imported comics became inaccessible, leaving gaps to be filled; Jijé drew a considerable amount of Spirou's content in those days, including a few off-label episodes of the American comics the magazine was running at the time, like Superman. By the time the war ended, Jijé had the authority to appoint younger artists like Franquin to fill slots, thus seeding the future of Spirou in the trodden dirt of war. Peyo followed several years later, having met Franquin & company as a teenage animator during the occupation.

Still, formative an artistic age as it was, it couldn't have been the best time for instilling pride in civic coordination in a pair of young men, to say nothing of respect for His Majesty, who was deported by the German military government in 1944, and, following the end of the war, settled in Switzerland while the returned Belgian government set about determining whether he was a literal traitor (A: no). His eventual return to the domain in 1950 was marked with violence and civil disoedience, particularly in the Wallonia region, and he abdicated the throne in 1951.

Yet while it's probably not a stretch to position Peyo's & Delporte's vision of governance-as-free-for-all as purely a product of the domestic upheaval which, in its way, brought them to the place they were, there were separate breakdowns going on as the comic itself was drawn, farther away, but still close.

***

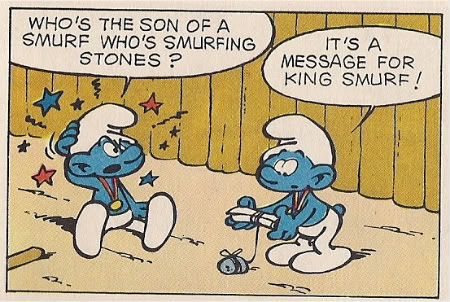

King Smurf is on edge after the jailbreak, and his enforcers are attentive to even the slightest departure from the usual. Still, Smurfs sometimes manage to slip away from the village, trusting that their faith won't get them killed by their exiled brothers out in the trees.

Serious shit those Smurfs are into. Covert activities have been sowing the seeds of discord in the village too:

Yes, they're threatening to kill him. Or, I dunno, maybe "Smurf to King Smurf" means "Voter Recall to King Smurf"; I don't even know how you read those things. Is it subtle shifts in the handwriting? A perfect in the 'S' the difference between libel and reverence? Oh the debates I have with my anime hug pillows!

Regardless, King Smurf clearly gets the message, and opts to put a crack forestry investigatory together the only way he knows how: by appealing to everyone's basest instincts.

I really do truly love that this comic is aimed squarely at kids. There's no respect for anything at all in here. Not military service, not heads of state, not the fundamentals of democracy... it's great! It's awesome, noisy slapstick paired up with bizarre fits of witty sophistication, all in a crispy pretzel cone of rampant anti-authoritarianism. How could the cartoon get so fucking saccharine? Smurfs have teeth! Shit out in the woods? It bites you.

So, King Smurf leads his decorated fellows out into the forest to smoke out the rebels. What results can best be described as a rib-tickling military quagmire (aren't they all?), with people falling into holes, getting soaked with water and opening strange gifts in the middle of nowhere to unhappy conclusions.

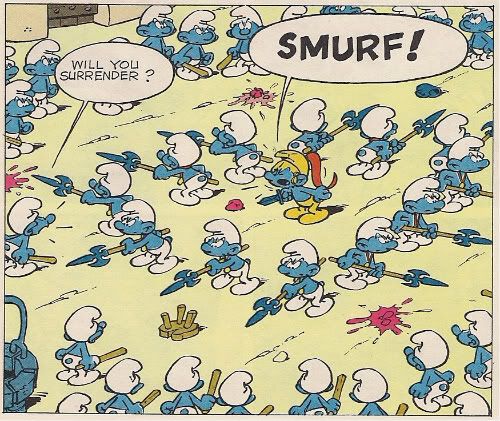

The campaign is a disaster. King Smurf and his men turn tail and retreat as the rebels laugh and jeer. Defections are evident. Still defiant, King Smurf declares that all Smurfs shall now join the military or face jail. A wall is erected around the Smurf Village. Nobody gets in or out.

A message from the other side is delivered.

Abdicate, Your Highness, or draw your sword. The King of the Smurfs opts for the latter.

It's time to get down to some serious killing.

***

Belgium's colonialist disposition was in for a shift as World War II ended. For our purposes, some symbolism can be dragged from the work of Hergé, whose Tintin in the Congo contained several unconcerned references to the colony's status as such in its 1931 initial printing, which were removed by the artist in an extensive 1946 revision.

Outside of comics, pressure for Congolise self-government was building as the '50s moved forward; riots erupted in 1959 upon Belgian prohibition of a meeting by the increasingly formidable ethnic association ABAKO, resulting in some allowance for Congolise participation in governance, and the subsequent formation of dozens of political parties.

Events passed with tremendous speed. Plans to transition the colony into independence compressed, and free elections were held in May of 1960. The Mouvement National Congolais-Lumumba performed well, and the formal handover of power occurred on June 30, 1960. However, not a week later, a mutiny broke out against remaining foreign military officers, leading to the entrance of the Belgian army and, by August, the secession of two areas -- the mining-rich province of Katanga, still close to Belgian industry, and the region of South Kasai -- and the intervention of the United Nations. This situation (and I'm wildly simplifying here) also led to prime minister Patrice Lumumba requesting aid from the Soviet Union to press into Kasai, after which strife exploded in the parliment and army chief of staff Joseph Mobutu, with support from the American CIA, ultimately took power in a military coup.

The struggle continued through the 1960s. In 1964, the year King Smurf began serialization, violent rebellions broke out, which again saw involvement by Belgium and the U.S. In 1965, the year the comic was published in a collected edition, Mobutu (who had previously suspended the parliment) launched a second coup and prohibited all political organizations save for his. This was the backdrop for the story's creation and release, in addition to the bloody division of Ruanda-Urundi into Rwanda & Burundi. The motif of elections leading to conflict seems perhaps informed by such current events.

Naturally, the comic's satire isn't directly on point. I speculate. And frankly, a noxious reading is possible from that perspective, a clucking of the tongue at those silly Smurfs thinking they can run things without the undemocratic wisdom of Papa around - my god, can names get any more paternalistic than "Papa"?

Yet maybe I'm wrong to look to the Smurf's feet for their secrets. Maybe the answer to everything is on top of their heads.

Those wilted cone things aren't their skulls, you know; they're Phrygian caps, and I'm not talking gallbladders. I mean headgear of antiquity, used in ancient Greek art as a symbol of foreignness, and in Roman culture as an accoutriment of freedom, worn by freedmen. Sometimes there was a martian connotation; if you should even encounter a Smurf running at you quoting Horace in Latin at the top of his lungs, the meaning will be clear. The caps were later adopted by the American and French Revolutions for their long-built association with liberty. The red cap was preferred, but putting Papa and his Smurfs together gives you something cumulative: the colors of both lands, red, white and blue.

And if indeed the Smurfs, as icons, as drawings, as mentioned above, are a distillation of accrued cartooning tropes, perfectly molded identities upon which endless human characteristics can be imprinted, the widest exposure of the Marcinelle school, grown from the dirt of World War II and wearing liberty caps and fighting in the midst of a democratic collapse in a time of post-colonialist democratic collapse, then - isn't their uniformity especially and awfully human? Isn't there a metaphor at work in these blue gnomes born it seems with freedom atop their brows?

Doesn't everyone want to be actualized? To be in control of themselves? And don't we still fall into groups, communities of desire or necessity, to our benefit and peril?

That's the real conflict of Smurf village, illustrated in King Smurf. To long to stand for yourself, but for individuality to be your downfall, and to become a collective, all again for freedom; resistance, rebellion, subjugation. Liberty atop the brow, all Smurf underneath, just lose Brainy's glasses and shave Papa's beard.

Er, and there's Smurfette, I guess, but she's not in this comic, and that's another story.

***

Thus:

What more needs to be said?

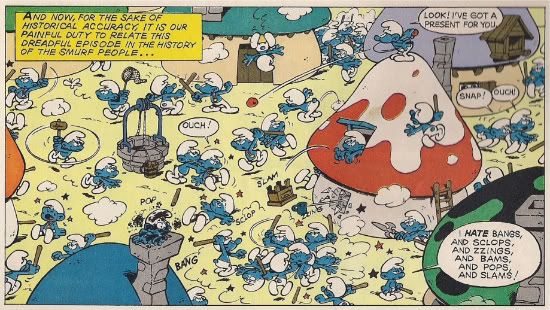

Do note, though, that while the Smurfs hold clubs and rocks and spears and things, and sometimes bite one another's asses, most of the actual warfare goes on via the not-very-deadly tomato, which Peyo nonetheless uses for maximum graphic detail, red on white. It's an impressive balancing act, maintaining an appropriateness for children while getting the point across without a lot of obfusication. I mean:

As the battle rages, some hot-blooded patriot gets the bright idea to raid Papa's lab, which we've long ago established contains a lot of explosive materials, no doubt stockpiled for the revolution Papa won't be heading, in that he is not a Communist. The bomb is lit, and chucked into the palace, and in a glorious flash of victory the walls of the oppressor come falling, mostly around Brainy Smurf, who was still locked inside. Ah, he's a big guy, he can take it.

Before long, the war's conclusion is certain. The final press is made. No quarter given. We're gonna see what color a Smurf bleeds. This had to happen. This is how you water a society.

And then, Papa walks in, before anyone's head seriously loses track of its shoulders. He's unhappy to an extent that even a green sack full of Euphorbium cannot counteract, not that he'd ever try that stuff.

I like the pike driven through the red-stained home on the left; they should have ended more episodes of the Get Along Gang with images like that.

Yep, with Papa back in town, order is soon restored. King Smurf volunteers to clean up the village all by himself, but soon every Smurf is jumping in to help. Everyone is happy, and democracy is rightfully relegated to the scrap heap of bad ideas. I mean, nobody comes out and says that, no, but it's not left unclear that Smurf Village probably won't be seeing another election day for a quite a while; what's the need, with Papa back? I mean it: the comic concludes with the heroes rejecting democracy and it's a happy ending.

All right, ok, but what are the Smurfs? Politically? Like, isn't this a weaselly ending, the whole book talking all sorts of shit about the perils of authority and then spinning around and having the Smurfs just agree with whatever Chairman Papa says?

Jesus, 'Papa' does have that paternalist bite.

Which makes sense, because, on the surface, not as icons, not symbols or allegories, without thinking about it too hard - the Smurfs are children, in the way their audience is children. And surely children need to listen to their parents when it's time to go to bed.

But that's the only authority this comic nods toward as valid. The parent, calling an end to playtime, and scolding the kiddies for acting like "human beings," which we might as well call adults, specifically the adults a child witnesses beyond their parents' adoration. Don't grow up to be like them. Don't make their mistakes.

Someday they'll be old enough to know their parents hold some responsibility. Until then, you know what they can do with the shit stupid robes of those awful motherfuckers?

Sadly, this wouldn't be the final conflict to bedevil the good Smurf Village.

***

In 2005, a certain commercial for UNICEF aired on European television.

Produced with the agreement of the family of Peyo, who died in 1992, the short piece depicted happy, dancing Smurfs and their delightful music annihilated by aerial bombing, their shouts of terror giving way the the squeals of Baby Smurf, a future bomb-thrower, an anticipatory gunman aimed, in potential, toward the next village, the next nation, sitting in the center of a heap of blue corpses, their faces blackened in that Marcinelle manner.

Witnessing this terrible scene, it is not difficult to imagine the tiny Smurfling growing to find a mask and wear it, and hide among the trees. This time it won't be tomatoes, and there's no Papa left to stop it.

The ad campaign was initiated to raise money for the rehabilitation of child soldiers in Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the former colonies of Belgium.

And history's great burden is that it never does end.

***

Nothing ever seems to end.